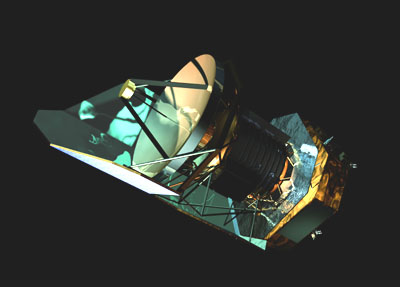

ESA’s Herschel space observatory is expected to exhaust its supply of liquid helium coolant in the coming weeks after spending more than three exciting years studying the cool Universe. Herschel was launched on 14 May 2009 and, with a main mirror 3.5 m across, it is the largest, most powerful infrared telescope ever flown in space.

A pioneering mission, it is the first to cover the entire wavelength range from the far-infrared to submillimetre, making it possible to study previously invisible cool regions of gas and dust in the cosmos, and providing new insights into the origin and evolution of stars and galaxies.

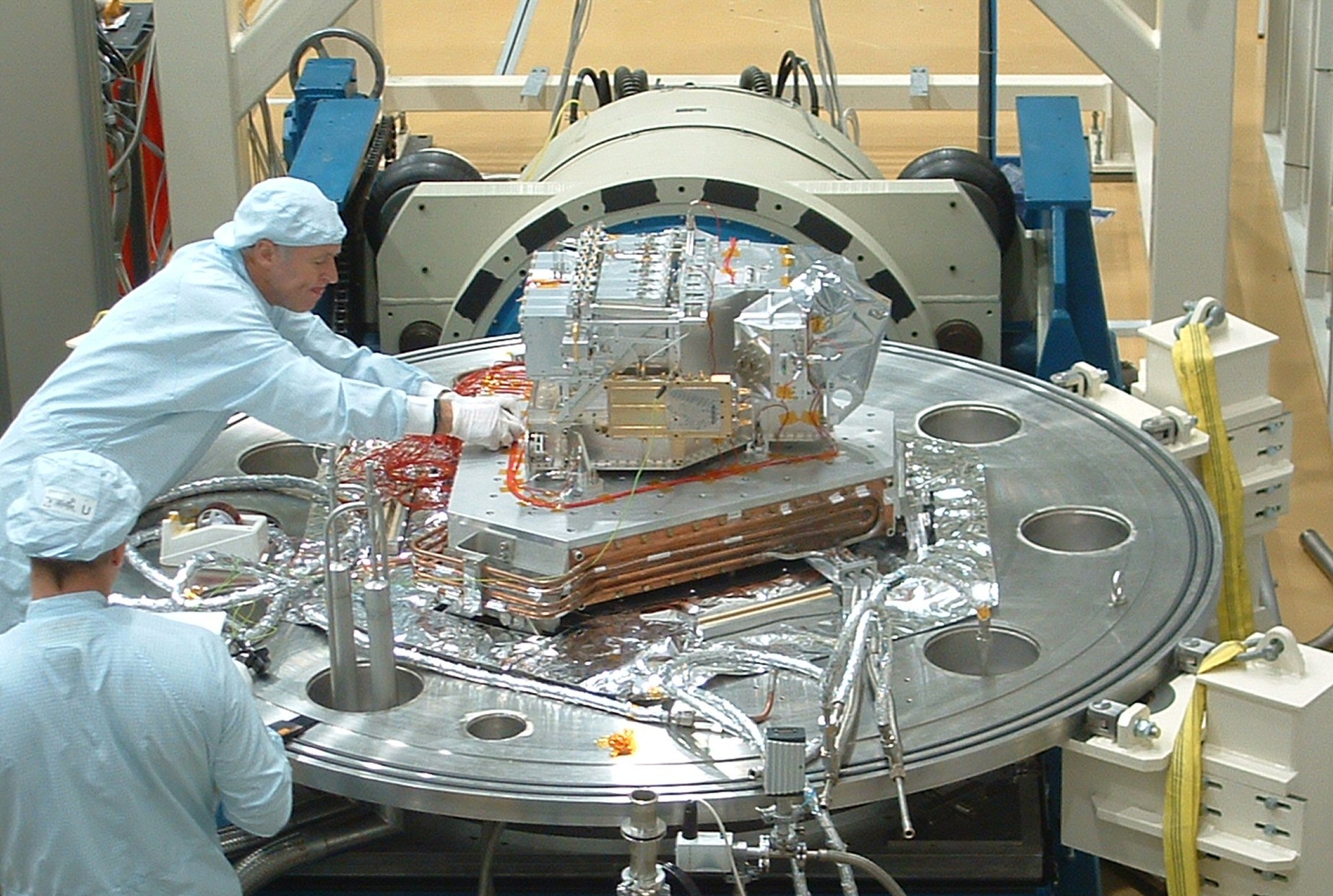

Herschel carries three science instruments: the high resolution spectrometer HIFI and the far-infrared camera’s/spectrometers PACS and SPIRE. All three instruments are cooled to –271ºC inside a cryostat filled with liquid superfluid helium.

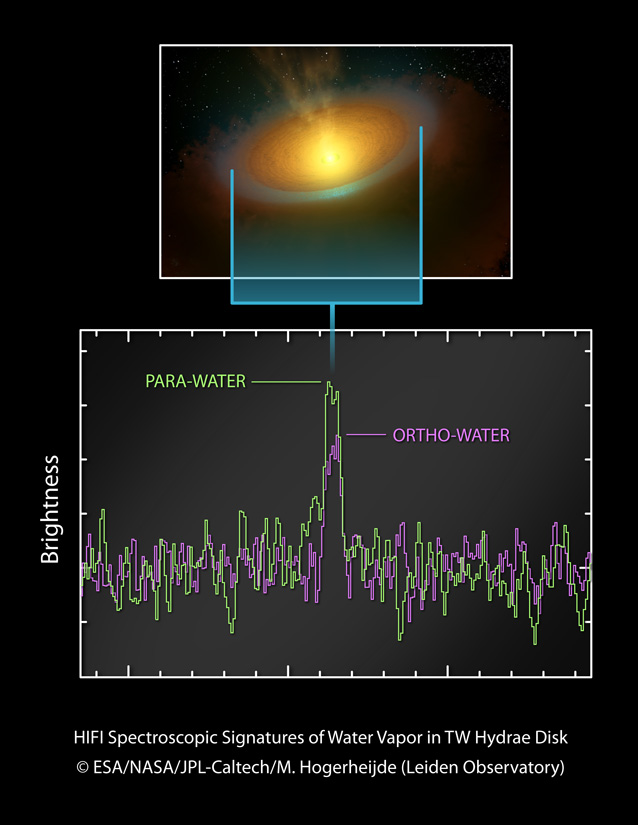

HIFI

HIFI found for example evidence for the hypothesis that our water comes from comets. Frank Helmich (SRON, RUG), HIFI Principal Investigator: “With HIFI we found water vapour from the comet Hartley-2, a comet from the Kuiper Belt, with almost exactly the same composition as the water of Earth’s oceans. The discovery revives the idea that many comets from the Kuiper Belt collided billions of years ago with a young and cooled down Earth, and that the water ice on these comets formed the water in our planet’s seas.”

There were also new discoveries in the area of star formation. “HIFI was the first instrument to find cold water vapour in the earliest stages of star formation,” says SRON-researcher Floris van der Tak. “The star doesn’t exist as yet, but we saw water vapour flowing in the direction of the centre of the cloud. We could deduce that the cloud contains large amounts of water. This suggests that Earth-like planets with oceans may be more abundant in the universe than we thought.”

Cryostat

In order to make such sensitive far-infrared observations, the detectors of the three science instruments – two cameras/imaging spectrometers and a very high-resolution spectrometer – must be cooled to a frigid –271°C, close to absolute zero. They sit on top of a tank filled with superfluid liquid helium, inside a giant thermos flask known as a cryostat.

The superfluid helium evaporates over time, gradually emptying the tank and determining Herschel’s scientific life. At launch, the cryostat was filled to the brim with over 2300 litres of liquid helium, weighing 335 kg, for 3.5 years of operations in space.

Helium runs out

Indeed, Herschel has made extraordinary discoveries across a wide range of topics, from starburst galaxies in the distant Universe to newly forming planetary systems orbiting nearby young stars. However, all good things must come to an end and engineers believe that almost all of the liquid helium has now gone. It is not possible to predict the exact day the helium will finally run out, but confirmation will come when Herschel begins its next daily 3-hour communication period with ground stations on Earth.

“It is no surprise that this will happen, and when it does we will see the temperatures of all the instruments rise by several degrees within just a few hours,” says Micha Schmidt, the Herschel Mission Operations Manager at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

The science observing programme was carefully planned to take full advantage of the lifetime of the mission, with all of the highest-priority observations already completed. In addition, Herschel is performing numerous other interesting observations specifically chosen to exploit every last drop of helium.

“When observing comes to an end, we expect to have performed over 22 000 hours of science observations, 10% more than we had originally planned, so the mission has already exceeded expectations,” says Leo Metcalfe, the Herschel Science Operations and Mission Manager at ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Madrid, Spain.

Treasure trove

“We will finish observing soon, but Herschel data will enable a vast amount of exciting science to be done for many years to come,” says Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel Project Scientist at ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. “In fact, the peak of scientific productivity is still ahead of us, and the task now is to make the treasure trove of Herschel data as valuable as possible for now and for the future.”

Herschel will continue communicating with its ground stations for some time after the helium is exhausted, allowing a range of technical tests. Finally, in early May, it will be propelled into its long-term stable parking orbit around the Sun.

Consortia

Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA. HIFI is built and developed by a consortium lead by SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, with important contributions from TNO and small and medium-sized enterprises like Mecon.