De infrarood-ruimtetelescoop SPICA is doorgedrongen tot de laatste selectieronde voor een middelgrote missie (M5) van de Europese ruimtevaartorganisatie ESA. Het SPICA-consortium en ESA gaan het voorstel, dat onder leiding van SRON is ingediend in samenwerking met Japan (JAXA), nu volledig uitwerken. Bij een definitieve selectie uit de laatste drie kandidaten, verwacht in 2021, gaat SPICA de ontstaansgeschiedenis en evolutie van sterrenstelsels in kaart brengen, van tien miljard jaar geleden tot nu. Sterrenkundigen kijken met de telescoop straks ook naar de condities voor de geboorte van planeetsystemen die lijken op ons eigen zonnestelsel.

Ruimtetelescoop SPICA bekijkt het heelal in infrarood licht. Die straling vliegt dwars door het ruimtestof heen dat overal in het universum aanwezig is en het zicht blokkeert voor telescopen die gevoelig zijn voor zichtbaar licht. Via infrarood licht kijken we door de stofsluiers heen, tot diep in het binnenste van sterrenstelsels, stervormende wolken en planeetsystemen in wording.

Astronomen willen sterrenstelsels bestuderen met SPICA (SPace Infrared telescope for Cosmology and Astrophysics) om erachter te komen welke processen hun ontstaan en evolutie reguleren. Al vroeg in de geschiedenis van het heelal, zo’n twaalf miljard jaar geleden, begonnen de eerste sterren zich te vormen in groepen die uiteindelijk uitgroeiden tot de eerste sterrenstelsels. Tijdens de eerste paar miljard jaar verliep dit proces steeds efficiënter, tot de activiteit ongeveer negen miljard jaar geleden piekte. Sindsdien nam de productie gestaag af. De reden voor deze af- en toename is nog onduidelijk. SPICA neemt de spectrale vingerafdrukken van enkele duizenden sterrenstelsels, verdeeld over de geschiedenis van het universum. Daaruit bepalen sterrenkundigen de condities in en rond die sterrenstelsels, en daarmee welke omstandigheden hun vorming en evolutie versnellen en vertragen.

Binnen onze eigen Melkweg zal SPICA sterren en planeetsystemen in wording bestuderen. Dat proces voltrekt zich diep in de sluiers van dichte gas- en stofwolken en kunnen we dus alleen in het infrarood goed volgen. Ook hierbij gebruiken we een spectrale vingerafdruk, waarmee we de omstandigheden bepalen in en rond de materieschijf waarin de planeten zich vormen. De vingerafdruk onthult welke moleculen en atomen de voornaamste ingrediënten zijn voor planeetvorming. SPICA kan daarbij vaststellen in welke delen van de planeetvormende schijf water in gas- of vaste vorm voorkomt en zo de ‘sneeuwlijn’ in kaart brengen. Van meer geëvolueerde planeetsystemen karakteriseert SPICA de buitenste asteroïdeschil—het ‘bouwafval’. In ons Zonnestelsel noemen we deze schil de Oortwolk. Dit geeft een direct inzicht in de ontstaansgeschiedenis van ons eigen zonnestelsel.

SAFARI

Een consortium geleid door SRON is verantwoordelijk voor het grootste en meest complexe instrument van SPICA: de ver-infrarood spectrometer SAFARI. Transition Edge Sensoren (TES) vormen het hart van SAFARI. Die sensoren zijn ontwikkeld door SRON en functioneren alleen optimaal bij minimale achtergrondruis van de telescoop.Om dat te bewerkstelligen wordt de SPICA-telescoop gekoeld tot slechts zes graden boven het absolute nulpunt. Dat maakt SPICA tot de gevoeligste telescoop ooit in het mid- en ver-infrarood.

Bijna twintig instituten uit vijftien landen werken mee aan het SAFARI-project. Ieder instituut levert haar eigen expertise. SRON is systeemarchitect en eindverantwoordelijke, en levert samen met de Verenigde Staten en het Verenigd Koninkrijk de TES-expertise. Verder levert Frankrijk het koelsysteem, Spanje de optica en de behuizing en Canada een interferometer. Andere bijdragen komen uit België, Denemarken, Duitsland, Ierland, Italië, Japan, Oostenrijk, Taiwan, Zweden, en Zwitserland.

SAFARI bestrijkt het golflengtegebied van 34 tot 230 micrometer met ruim drieduizend TES-detectoren. De telescoop focust de ver-infraroodstraling op het SAFARI-instrument, dat het met een tralie in verschillende kleuren uiteen splitst. Hierdoor ziet iedere sensor een iets andere kleur. Voor meer detail in deze spectrale vingerafdruk heeft SAFARI een zogeheten Martin-Puplett interferometer, die in het lichtpad geschoven kan worden. SAFARI heeft een speciale koeler om de TES-detectoren af te koelen tot vijftig milligraad boven het absolute nulpunt. Het instrument kan ruim honderd keer zwakkere bronnen bestuderen dan tot nu toe mogelijk was met de beste telescoop.

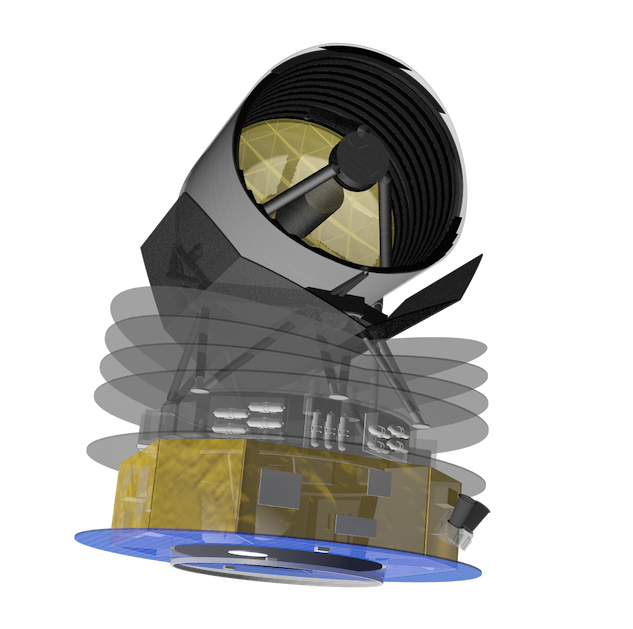

SPICA

Naast SAFARI telt de SPICA-telescoop nog twee instrumenten om het spectrum tussen mid- en ver-infrarood licht bestrijken: straling van 12 tot 350 micrometer golflengte. Japan levert een combinatie van een mid-infraroodcamera en spectrometer, terwijl een Europees consortium geleid door Frankrijk een kleine ver-infrarood camera en polarimeter maakt.

SPICA is een samenwerkingsproject van ESA en de Japanse ruimtevaartorganisatie JAXA. ESA is in de plannen eindverantwoordelijk voor de missie, de telescoop, de bouw van de satelliet-supportsystemen en de integratie van alle onderdelen. Japan levert het koelsysteem en is verantwoordelijk voor het integreren van de ‘payload’—het platform met de koude telescoop en instrumenten. Daarnaast verzorgt Japan de lancering van de satelliet, met een H3-raket. De drie instrumenten worden door consortia van wetenschappelijke onderzoeksinstituten gebouwd, met bijdragen van over de hele wereld.

Een internationaal consortium onder leiding van SRON diende het SPICA-voorstel in 2016 in bij ESA in het kader van de vijfde call voor middelgrote missies (M5) in het Cosmic Vision-programma. SPICA had concurrentie van 25 voorstellen die meedongen naar het M5-budget van 550 miljoen euro. Uiteindelijk is SPICA samen met twee andere missies, THESEUS en EnVision, geselecteerd voor de laatste ronde, waarin via drie parallelle detailstudies het beste voorstel wordt uitgekozen. Naar verwachting kiest ESA op basis van die studies in 2021 definitief haar M5-missie, die rond 2030 de ruimte in gaat.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Space telescope SPICA to final selection round

Infrared space telescope SPICA has advanced to the final selection round for a medium class mission (M5) of the European Space Agency ESA. The SPICA consortium and ESA will now fully work out the proposal, which was submitted under SRON leadership in close collaboration with Japan (JAXA). If the mission is picked out of the final three candidates, expected in 2021, SPICA will map the origin and evolution of galaxies, from ten billion years ago until now. Astronomers will also use the telescope to study the conditions required for the birth of planetary systems similar to our own Solar System.

Space telescope SPICA studies the Universe in infrared light. This radiation shoots straight through space dust, which is present all across space and blocks the view for telescopes that are sensitive to visible light. Using infrared light we peek through the dust veils, deep into the inner reaches of galaxies, starforming clouds and planet forming systems

Astronomers want to study galaxies with SPICA (SPace Infrared telescope for Cosmology and Astrophysics) to find out which processes regulate their origin and evolution. Early in the history of the Universe, about twelve billion years ago, the first stars and galaxies started to form. In the next few billion years the process of formation and evolution sped up, becoming increasingly more efficient, until that activity peaked about nine billion years ago. Since then, the production of these megastructures has been slowing down continuously. The cause for the increase, peak and subsequent decrease of galaxy formation efficiency is still the subject of speculation. SPICA takes spectral ‘fingerprints’ of many thousands of galaxies spread over cosmic time. From these, we will be able to accurately probe the physical conditions in and around these galaxies, and thus determine the factors that govern their formation and evolution.

Within our own Galaxy, SPICA will provide detailed insight into the formation process of stars and planetary systems. This happens deep inside dense dusty clouds and can only be traced well in the infrared. Also here we use a spectral fingerprint, to determine the physical conditions in and around the planet forming disk. It reveals which atoms and molecules are the essential ingredients for planet formation. In addition, SPICA will allow us to establish where in the planet forming disk water is solid or gaseous, so we can chart the ‘snowline’. For more evolved planetary systems, SPICA characterizes the outer asteroid ring—the ‘construction waste’. In our Solar System we call this ring the Oort cloud. It gives direct insight into the origins of our own Solar System.

SAFARI

A consortium led by SRON is responsible for SPICA’s biggest and most complex instrument: the far-infrared spectrometer SAFARI. Transition Edge Sensors (TES) form SAFARI’s heart. These detectors are developed by SRON and only reach their maximum potential if there is minimum background noise from the telescope. Therefore SPICA is constantly cooled to six degrees above absolute zero. It makes SPICA the most sensitive telescope ever in the mid- and far-infrared.

Almost twenty institutes from fifteen countries work on the SAFARI project. Each institute brings its own expertise. SRON is system architect, carries final responsibility and delivers together with the United States and the United Kingdom the TES expertise. France provides the cooling system, Spain the optics and instrument structure and Canada an interferometer. Other contributions come from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland and Taiwan.

SAFARI covers the wavelength area between 34 and 230 micrometer using over three thousand TES detectors. The telescope focusses the far-infrared radiation on the SAFARI instrument, which disperses it into different colors using a grating. For more detail in the spectral fingerprint, SAFARI has a so-called Martin–Puplett interferometer, which can be inserted into the light path. SAFARI also has a dedicated cooler to cool the TES detectors to fifty milliKelvin. The instrument can study sources weaker by more than two orders of magnitude than was possible ever before.

SPICA

Apart from SAFARI, the SPICA telescope contains an additional two instruments to cover the spectrum between mid- and far-infrared: radiation of 12 to 350 micrometer wavelength. Japan provides a combination of a mid-infrared camera and spectrometer, while a European consortium led by France builds a small far-infrared camera and polarimeter.

SPICA is a collaboration between ESA and the Japanese space agency JAXA. ESA is responsible for the mission, the telescope, building the satellite support systems and integrating all parts. Japan provides the cooling system and is responsible for integrating the ‘payload’—the platform with the cold telescope and instrument. Moreover, Japan takes care of launching the satellite, with an H3 rocket. The three instruments are built by consortia of scientific research institutes, with contributions from all over the globe.

In 2016, an international consortium led by SRON submitted the SPICA proposal to ESA as part of the fifth call for medium class missions (M5) in the Cosmic Vision program. A total of 25 proposals competed for the M5 budget of 550 million euro. Together with two other missions, THESEUS and EnVision, SPICA is now selected for the final round, in which three parallel detailed studies will determine the best proposal. ESA is expected to select its M5 mission in 2021. The mission should be launched around 2030.