Het Nederlandse ruimte-instrument TROPOMI heeft sinds haar lancering in 2017 de nodige kosmische straling te verwerken gekregen. Een analyse van de kortgolvige infrarood detector, gericht op de detectie van methaan en koolmonoxide, toont aan dat 98.7% van de pixels nog goed werkt. Spontaan herstel van pixels draagt hier aan bij. Publicatie in Measurement Science and Technology.

complete wereldkaart

TROPOMI vliegt sinds 2017 elke negentig minuten rond de aarde. Terwijl het van pool naar pool zweeft, blijft de wereld eronder doordraaien, zodat TROPOMI met elke baan geruisloos een nieuwe strook aarde scant. Uiteindelijk levert dat een complete wereldkaart op van onder meer methaan en koolmonoxide in de atmosfeer, gemeten met de detector voor nabij-infrarood.

kosmische straling

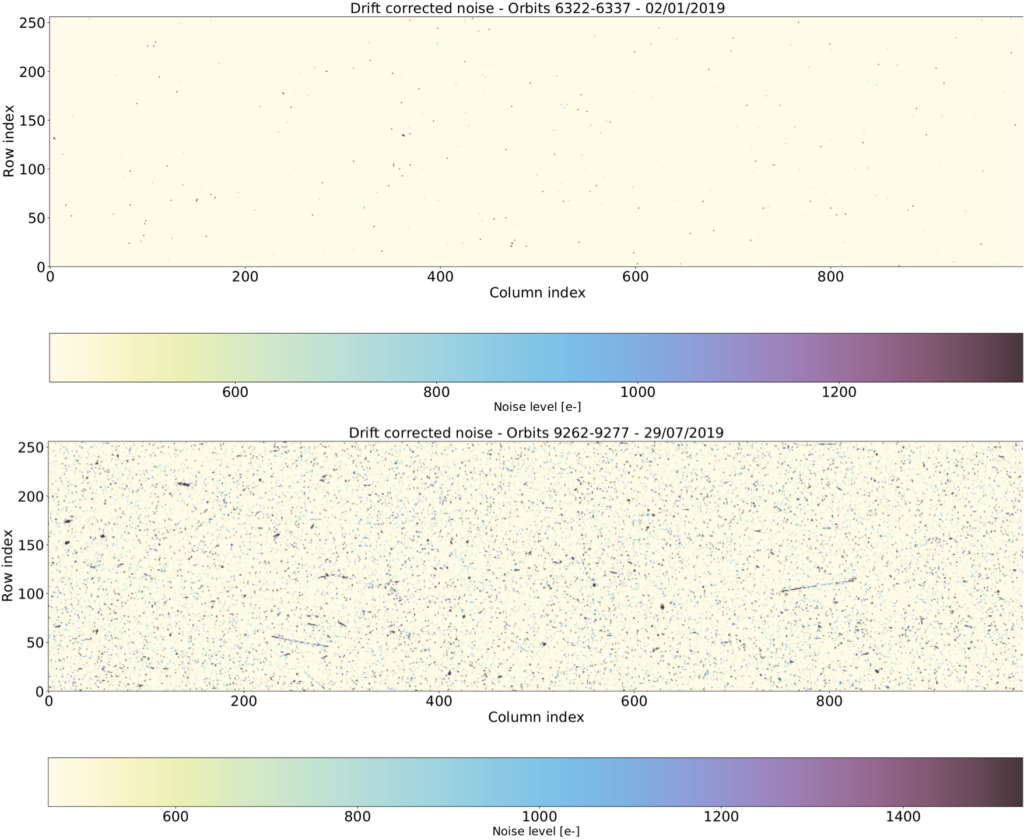

Zo vredig als satellieten door de ruimte dwalen, zo gewelddadig is de kosmische straling die vanaf de Zon en vanuit de Melkweg op ze inslaat. We kennen deze geladen deeltjes in hun elegante verschijning als ze de aardmagnetische veldlijnen volgen naar de polen en zich tonen als het noorderlicht. Maar ruimtedetectoren lopen risico op beschadigingen in hun materiaal als ze daarover vliegen. Dit risico is nog groter als ze door de Zuid-Atlantische Anomalie boven Zuid-Amerika vliegen, waar het beschermende schild van het aardmagnetisch veld een stuk lager hangt dan de vlieghoogte van TROPOMI.

pixels onbeschadigd

Ondanks deze ruimte-versie van de Bermudadriehoek blijken de pixels in TROPOMI’s methaandetector vrijwel onbeschadigd te blijven. SRON is verantwoordelijk voor de monitoring van de detector en concludeert in een publicatie in Measurement Science and Technology dat altijd minimaal 98.7% van de pixels gezond is. Dit komt onder meer doordat de meerderheid van de beschadigde pixels spontaan herstelt.

spontaan herstel

‘De detector is gemaakt van een halfgeleider met een kristalstructuur,’ zegt eerste auteur Tim van Kempen (SRON). ‘Kosmische deeltjes beschadigen de pixels door het verstoren van die structuur. Opwarmen en afkoelen kan het kristal repareren, zoals een barst in een ijsblokje hersteld wordt door smelten en opnieuw invriezen. Alleen werkt onze detector bij 130 graden onder nul en is opwarmen het laatste wat je wilt. Gelukkig zien we nu dat 95% van de pixels spontaan herstelt. Dat is ook goed nieuws voor toekomstige ruimtemissies, want dit spontane herstel kenden we nog niet bij de lage temperaturen die ruimtedetectoren vaak nodig hebben.’