(English follows Dutch)

Wetenschappers ontwikkelen supergeleidende detectoren (MKIDs) om uit het zwakke schijnsel van exoplaneten een spectrum te ontwaren. Nu zien onderzoekers van SRON en de TU Delft bij hun MKIDs een honderdmaal lagere ruis dan gedacht. Het levert een nieuw natuurkundig inzicht op: de samenhang tussen het aantal quasideeltjes en hun levensduur vervalt. Publicatie in Physical Review B.

Exoplaneten schijnen zo zwak aan de hemel dat hun licht onze telescopen bereikt in de vorm van individuele fotonen. Om die te detecteren ontwikkelen SRON-wetenschappers een detectietechniek genaamd Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors, kortweg MKIDs. Die worden zo koud gemaakt dat er supergeleiding ontstaat, waarbij elektronen samen Cooperparen vormen en zo de intrinsieke elektrische weerstand van het materiaal omzeilen. Inkomende fotonen breken de Cooperparen op in quasideeltjes. Op basis daarvan herleiden MKIDs welke energie het foton had.

Zoals bij elke detectietechnologie zorgt ruis voor beperkingen in de gevoeligheid. Bij MKIDs ontstaat ruis doordat thermische fluctuaties zorgen voor het continu opbreken en recombineren van quasideeltjes. Als een zwak signaal van een exoplaneet slechts weinig Cooperparen opbreekt, verdrinkt het signaal van de resulterende quasideeltjes in deze quasideeltjes-ruis.

Toen SRON-wetenschappers, in onlangs gepubliceerd onderzoek, de gevoeligheid van hun MKID met factor 2,5 verhoogden door weglekkende energie van invallende fotonen langer vast te houden met een membraan, zouden ze daar met de standaard verwachte ruis eigenlijk niets aan hebben. Maar tot hun verbazing zagen ze dat de ruis een factor 100 lager lag dan verwacht. Het team was in staat om dit voor het eerst te zien doordat het membraan niet alleen de gevoeligheid van de detector zelf had verhoogd, maar ook de gevoeligheid waarmee tijdens testen de ruis kon worden gemeten. Bovendien vereist het nieuwe ontwerp een minder krachtig uitleessignaal, wat de detector minder verstoort. Zo bleek dat ze straks in de ruimte wel degelijk iets gaan hebben aan de 2,5-maal zo hoge precisie.

Het lijkt erop dat de ruis zo laag is omdat de samenhang tussen het aantal quasideeltjes en hun levensduur wegvalt bij de lage temperatuur (-273°C) waarop MKIDs opereren. Tot nu toe zagen natuurkundigen steeds dat hoe meer quasideeltjes er zijn, des te sneller ze elkaar vinden en opnieuw Cooperparen vormen, en dus hoe korter ze leven. Nu SRON-onderzoekers, onder leiding van Pieter de Visser (SRON/TU Delft), deze ruis in MKIDs nauwkeurig in kaart hebben gebracht, blijkt deze wetmatigheid niet meer van toepassing.

‘Die samenhang valt weg, quasideeltjes leven dus korter dan het gemeten aantal quasideeltjes suggereert’, zegt eerste auteur Steven de Rooij (SRON/TU Delft). ‘We denken dat de quasideeltjes vast komen te zitten en dus niet meer bijdragen aan de ruis.’ De Visser: ‘Behalve het verzilveren van onze 2,5-maal hogere precisie, betekent de veel lagere ruis ook een fundamentele natuurkundige ontdekking. De ontkoppeling van levensduur en aantal quasideeltjes is een nieuw effect dat ook andere wetenschappers kunnen gebruiken om hun detectoren flink te verbeteren.’

Publicatie

Steven A. H. de Rooij, Jochem J. A. Baselmans, Vignesh Murugesan, David J. Thoen, and Pieter J. de Visser, ‘Strong Reduction of Quasiparticle Fluctuations in a Superconductor due to Decoupling of the Quasiparticle Number and Lifetime’, Physical Review B

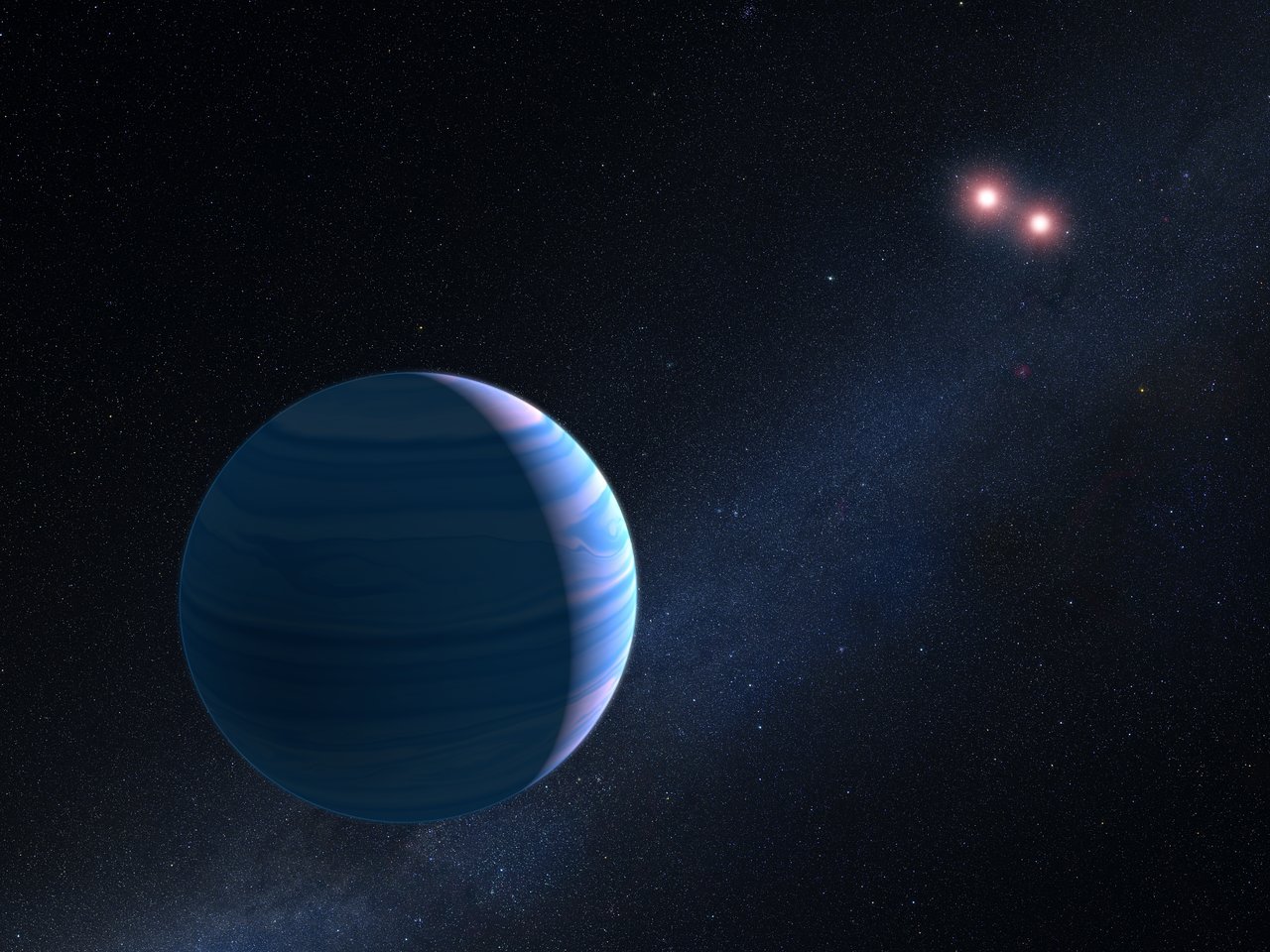

Credit header image: NASA, ESA, G. Bacon (STScI)

MKID detectors turn out to have 100 times lower noise

Scientists develop superconducting detectors (MKIDs) to discern the spectrum of exoplanets from their faint glow. Now researchers from SRON and TU Delft see a hundred times lower noise than previously thought. It provides a new fundamental physics insight: the relationship between the number of quasi particles and their lifetime vanishes. Publication in Physical Review B.

Exoplanets appear so dim in the night sky that their light reaches our telescopes in the form of individual photons. To detect these, SRON scientists are developing a detection technique called Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors, MKIDs for short. They cool them down to the point where superconductivity occurs; electrons form Cooper pairs and thereby avoid the intrinsic electrical resistance of the material. Incoming photons break the Cooper pairs up into quasiparticles. MKIDs use these to trace back the energy of each photon.

As with any detection technology, noise creates limitations to the sensitivity. In the case of MKIDs, noise arises from thermal fluctuations, which cause a continuous breaking up and recombination of quasiparticles. If a weak signal from an exoplanet breaks up only a few Cooper pairs, the signal from the resulting quasiparticles drowns in this quasiparticle noise.

When SRON scientists, in recently published research, increased the sensitivity of their MKIDs with a factor of 2.5 by using a membrane to retain leaking energy of incident photons, they would initially not benefit from it because of the standard expected noise. But to their surprise, they saw that the noise was a factor of 100 lower than expected. The team was able to see this for the first time because the membrane had increased not only the sensitivity of the detector itself, but also the sensitivity for measuring noise during testing. Moreover, the new design requires a less powerful readout signal, which disturbs the detector less. It means that space telescopes will in fact benefit from the 2.5 times higher precision.

It seems that the noise is so low because the correlation between the number of quasiparticles and their lifetime vanishes at the low temperature (-273°C) at which MKIDs operate. Until now, physicists have always observed that the more quasiparticles there are, the faster they find each other and form Cooper pairs again, and thus the shorter they live. Now that SRON researchers, led by Pieter de Visser (SRON/TU Delft), have accurately mapped out this noise in MKIDs, this law no longer appears to apply.

‘That correlation disappears, so quasiparticles live shorter than the measured number of quasiparticles suggests,’ says first author Steven de Rooij (SRON/TU Delft). ‘We think that the quasiparticles get stuck and therefore no longer contribute to the noise.’ De Visser: ‘In addition to making our 2.5 times higher precision relevant, the much lower noise also represents a fundamental discovery in physics. The decoupling of lifetime and number of quasiparticles is a new effect that also other scientists can use to significantly improve their detectors.’

Publication

Steven A. H. de Rooij, Jochem J. A. Baselmans, Vignesh Murugesan, David J. Thoen, and Pieter J. de Visser, ‘Strong Reduction of Quasiparticle Fluctuations in a Superconductor due to Decoupling of the Quasiparticle Number and Lifetime’, Physical Review B