(English follows Dutch)

In tegenstelling tot onze Melkweg hebben sommige sterrenstelsels een actief zwart gat in hun centrum dat krachtige gasstromen wegblaast. Maar we weten nog weinig over hun oorsprong en wat ze teweeg brengen. ESA’s toekomstige röntgenmissie Athena gaat hier verandering in brengen. In voorbereiding op de lancering volgend decennium hebben astronomen van SRON en de UvA nu een nieuwe methode ontwikkeld om Athena te gebruiken om deze gasstromen te bestuderen.

Sterrenkundige foto’s zijn vaak bezaaid met sterren uit de Melkweg. Maar pas op, soms zit er een wolf in schaapskleren tussen. In plaats van simpele sterren zijn sommige stippen eigenlijk het centrum van een compleet sterrenstelsel. Ze bewaren een grote afstand om zich voor te doen als een vage stip en op te gaan in de massa. Daarmee hebben ze astronomen decennialang voor de gek weten te houden, tot aan de jaren ’50, en daarom noemen we ze quasi-stellar objects, of kortweg quasars. Sterrenkundigen ontdekten dat het spectrum van sommige stippen erg roodverschoven was, wat duidt op een verre afstand waarvandaan een ster onzichtbaar zou zijn vanaf de aarde.

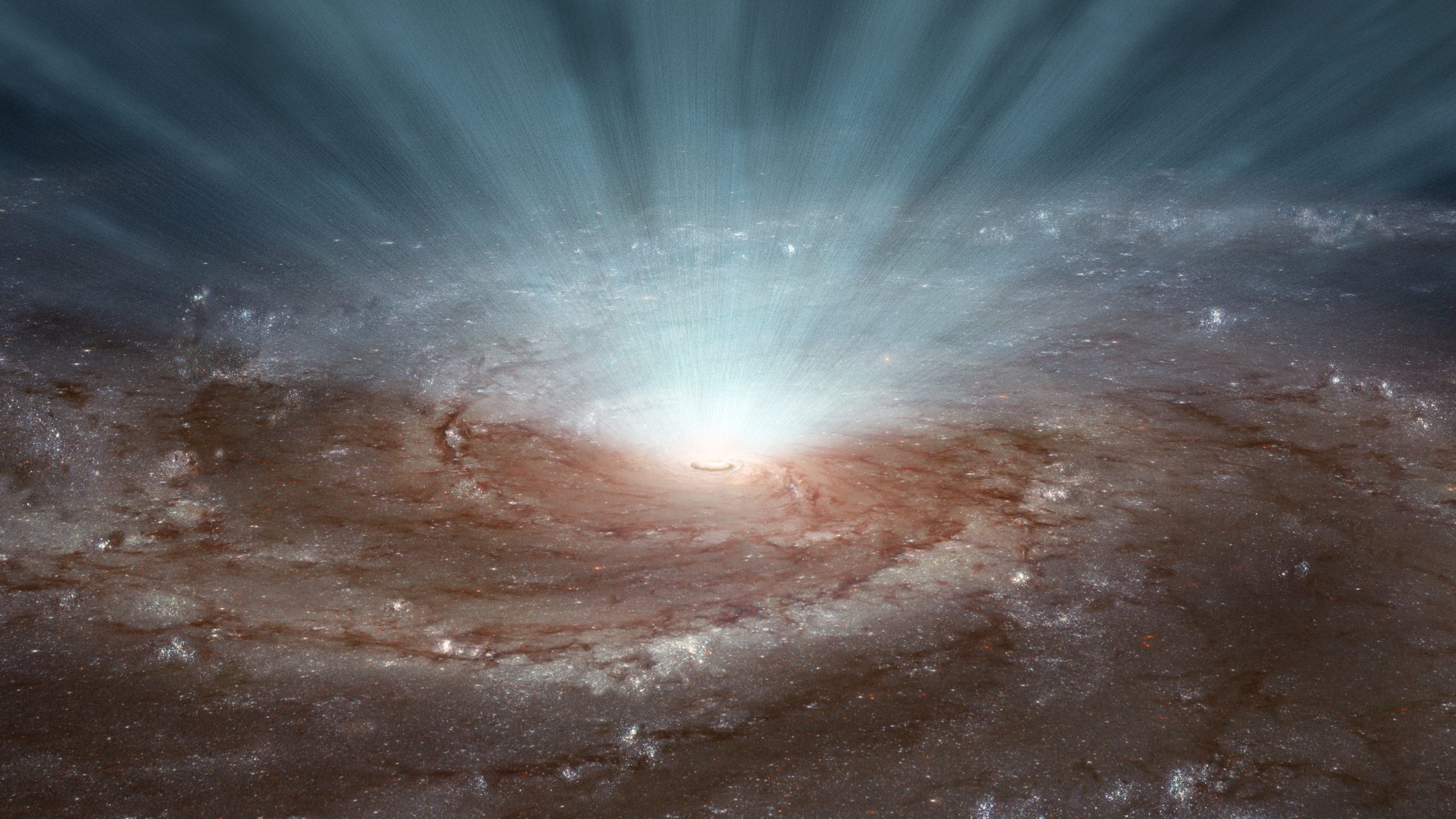

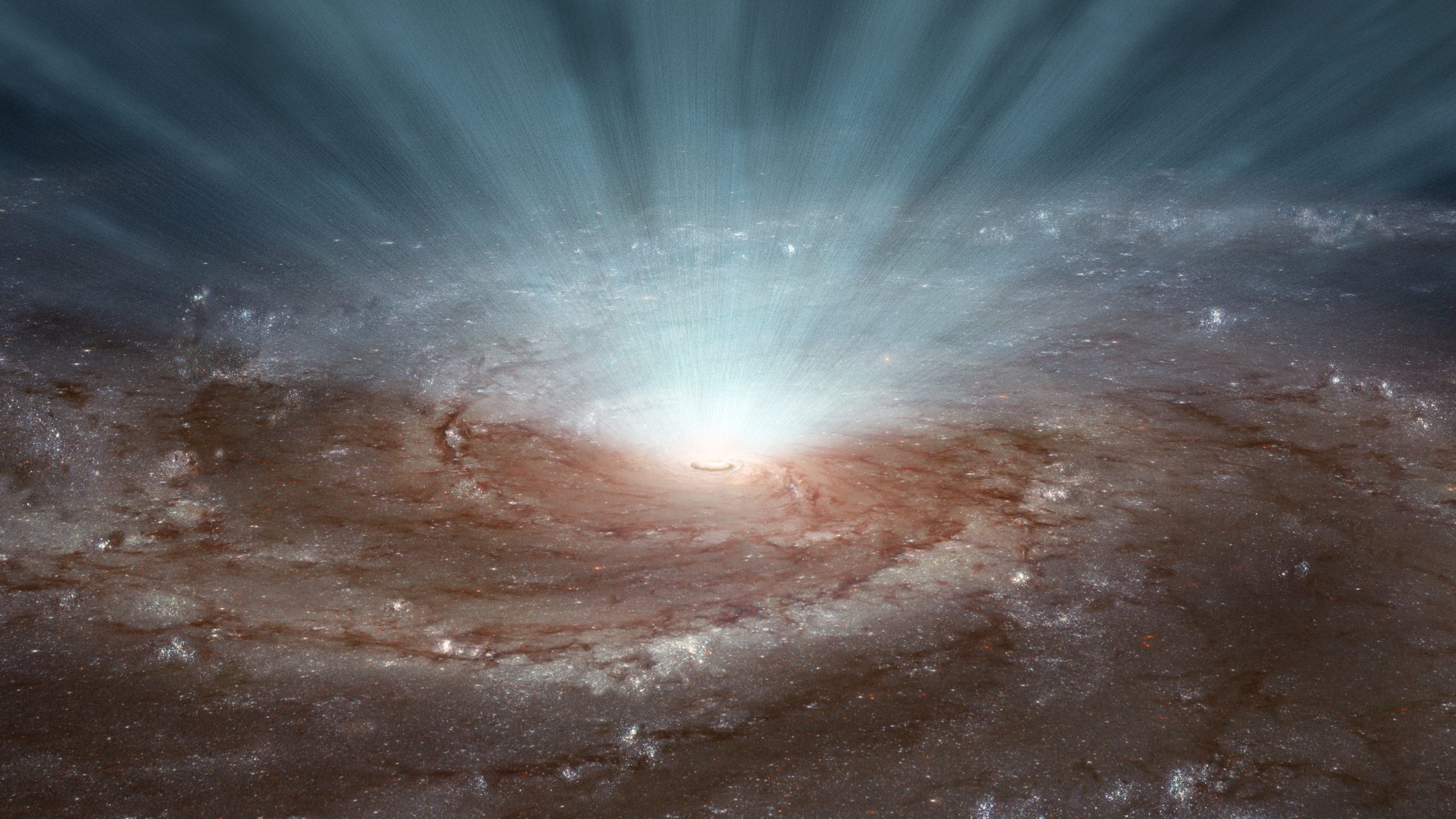

Onderschrift afbeelding: Artist impression van een actief superzwaar zwart gat in het centrum van een sterrenstelsel dat gasstromen wegblaast. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Uiteindelijk realiseerden astronomen zich dat het licht van quasars moet komen vanuit de kernen van sterrenstelsels—genaamd Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN)—waarschijnlijk aangedreven door superzware zwarte gaten. Kosmologische modellen voorspellen dat deze AGN de motoren zijn die de levensloop van sterrenstelsels veranderen, door grote hoeveelheden materiaal uit hun omgeving aan te trekken en weer wegblazen.

Elisa Costantini en haar team bij SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, onder wie Anna Juranova, en in samenwerking met Phil Uttley van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, bestuderen deze gasstromen vanuit AGN met gebruik van röntgentelescopen in de ruimte. In voorbereiding op de lancering van ESA’s nieuwe röntgenmissie Athena—die wordt gelanceerd in de jaren 2030 en met een substantiële bijdrage van SRON—heeft het team een nieuwe methode ontwikkeld om AGN-gasstromen te bestuderen. De helderheid van een AGN kan sterk variëren, vooral in het röntgendeel van zijn spectrum. De onderzoekers gaan Athena’s spectra gebruiken om te zien hoe de gasstromen reageren op deze helderheidsvariaties.

‘Uiteindelijk willen we begrijpen wat de gasstromen aandrijft en wat ze teweegbrengen binnen hun sterrenstelsel,’ zegt eerste auteur Juranova. ‘Daarvoor moeten we de dichtheid en locatie kennen van de gasstroom. En om dat te weten hebben we informatie nodig over de tijdschaal waarop het licht van de AGN het uitstromende gas ioniseert. Dankzij onze simulaties hebben we een nieuwe manier gevonden om dit te meten in gasstromen met verschillende eigenschappen. Wanneer we de echte data van Athena krijgen, kunnen we die vergelijken met onze modellen en bepalen welke het beste past bij de observaties.’

Om de gasstromen te identificeren op basis van hun gedrag, gebruikt het team zogenoemde frequentie-analyse. Juranova: ‘Vergelijk het met de temperatuur in Nederland. Die gaat op en neer in een dagelijkse cyclus, maar ook in een jaarlijkse cyclus. Met de analyse die we gebruiken kun je makkelijk de verschillende type veranderingen onderscheiden, omdat ze op de frequenties van die twee cycli plaatsvinden. En dat is erg handig omdat we zo elk proces individueel kunnen bestuderen. Op dezelfde manier verandert het licht van de AGN door de tijd heen vanwege processen die op verschillende tijdschalen plaatsvinden, van uren tot jaren, en dus helpt ook daar de frequentie-analyse om te begrijpen wat er gebeurt.’

Publicatie

A. Juránová, E. Costantini, P. Uttley, ‘Spectral-timing of AGN ionized outflows with Athena’, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

New method to study outflows from galactic centers in preparation for Athena

Unlike our Milky Way, some galaxies have an active black hole in their center driving powerful outflows of gas. But we know very little about their impact and origin. ESA’s future X-ray mission Athena will change this. In preparation for the launch in the 2030s, astronomers from SRON and UvA have now developed a new method to use Athena to study these outflows.

Astronomical pictures are often spangled with stars from the Milky Way. But be careful to trust your eyes, because some of them are imposters. Instead of simple stars, some dots are in fact centers of entire galaxies. They keep a large distance to appear as a faint dot and blend in with the stars. This trick has fooled astronomers for decades, until the 1950s, which is why we call them quasi-stellar objects, or quasars for short. Astronomers discovered that the spectrum of some dots was highly redshifted, indicating a large distance at which a star would be invisible from earth.

Caption header image: Artist impression of a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy driving outflows of gas. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Eventually, astronomers realized that the light from quasars must come from the centers of galaxies—called active galactic nuclei (AGN)—probably powered by a supermassive black hole. Cosmological models predict that these AGN are the powerhouses altering the evolution of galaxies, by attracting and ejecting massive amounts of material from their vicinity.

Elisa Costantini and her team at SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, including Anna Juranova, and in collaboration with Phil Uttley at the University of Amsterdam, are studying these outflows from AGN using X-ray space telescopes. In preparation for the launch of ESA’s new X-ray mission Athena—to be launched in the early 2030s and with a substantial contribution of SRON—the team has developed a new method to study AGN outflows. AGN brightness can be highly variable in time, especially in X-rays. The researchers will use Athena’s X-ray spectra to see how the outflows respond to these brightness variations.

‘In the end, we want to understand what drives the outflows and what impact they have on their host galaxy,’ says Juranova, who led the work. ‘For that, we need to know the density and location of the outflow. And to know that we need information about the timescale at which the light from the AGN ionizes the outflowing gas. Thanks to our simulations, we have found a way to measure this gas response in outflows with different properties. When we get the actual data from Athena, we compare them to our models and determine which one matches the observations best.’

To identify the outflows by their behavior, the research team uses frequency analysis. Juranova: ‘You can compare it to the temperature in The Netherlands. It goes up and down in a daily cycle, but also in a yearly cycle. With the analysis we use, you can easily disentangle the different types of changes, because they are happening at separate frequencies corresponding to these two cycles. And that is very helpful because we can then study these processes individually. Similarly, the light from the AGN changes in time because of processes happening at different timescales, from hours to years, and so the frequency approach helps us understand what is going on there.’

Publication

A. Juránová, E. Costantini, P. Uttley, ‘Spectral-timing of AGN ionized outflows with Athena’, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society