Volgens de conventionele theorie blazen lichte sterren als onze zon hun verschillende lagen zachtjes weg als ze sterven, waar zware sterren ontploffen als supernova’s. Maar om de een of andere reden zijn sterrenkundigen er nog niet in geslaagd supernova’s te vinden van sterren die zwaarder zijn dan achttien zonmassa’s. Een team onder leiding van SRON-sterrenkundigen heeft nu een nieuwe aanwijzing gevonden voor het bestaan van dit mysterie. Het onderzoek verschijnt in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

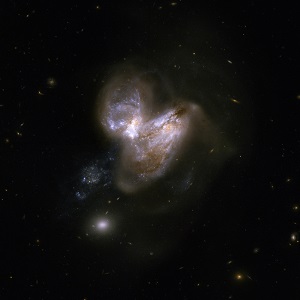

Het onderzoeksteam bestudeerde het sterrenstelsel Arp 299 met de XMM Newton-telescoop, waarmee ze de grote hoeveelheden verschillende chemische elementen wilden meten die normaal gesproken in de ruimte vrijkomen wanneer een zware ster ontploft. Toen de onderzoekers de gemeten hoeveelheden ijzer, neon en magnesium vergeleken met bestaande modelberekeningen die beschrijven hoe sterren hun directe omgeving verrijken, bleken die behoorlijk van elkaar te verschillen. “Dit is een nieuwe aanwijzing dat heel zware sterren niet als supernova’s eindigen,” zegt eerste auteur Junjie Mao (Hiroshima/Strathclyde/SRON). “Als we de verwachte bijdrage door supernova’s zwaarder dan 23 tot 27 zonmassa’s uit de modelberekening voor chemische verrijking weglaten, dan is het verschil tussen het model en onze waarnemingen ineens veel minder groot.”

Het onderzoeksteam bestudeerde het sterrenstelsel Arp 299 met de XMM Newton-telescoop, waarmee ze de grote hoeveelheden verschillende chemische elementen wilden meten die normaal gesproken in de ruimte vrijkomen wanneer een zware ster ontploft. Toen de onderzoekers de gemeten hoeveelheden ijzer, neon en magnesium vergeleken met bestaande modelberekeningen die beschrijven hoe sterren hun directe omgeving verrijken, bleken die behoorlijk van elkaar te verschillen. “Dit is een nieuwe aanwijzing dat heel zware sterren niet als supernova’s eindigen,” zegt eerste auteur Junjie Mao (Hiroshima/Strathclyde/SRON). “Als we de verwachte bijdrage door supernova’s zwaarder dan 23 tot 27 zonmassa’s uit de modelberekening voor chemische verrijking weglaten, dan is het verschil tussen het model en onze waarnemingen ineens veel minder groot.”

Sterrenkundigen begrijpen nog steeds niet waarom sterren van ongeveer achttien zonmassa’s niet gehoorzamen aan de conventionele theorie voor sterevolutie, en weigeren te ontploffen als supernova’s. “Een mogelijke verklaring is dat ze direct ineenstorten tot een zwart gat, zonder explosie,” zegt Aurora Simionescu (SRON). “We hebben nu nieuw bewijs dat de dood van zware sterren er wel eens heel anders uit zou kunnen zien dan we tot nu toe dachten. Het zou wel eens meer een zacht wegglijden kunnen zijn dan een kosmisch vuurwerk.”

Sterevolutie

Een pas geboren ster bestaat grotendeels uit waterstof, het lichtste element in het universum. De enorme zwaartekracht zorgt ervoor dat de druk in de sterkern oploopt, waardoor waterstof via kernfusie wordt omgezet in helium. Dit verschijnsel trekt als een brandende schil naar de buitenste lagen, waarbij een helium kern overblijft. Wanneer deze kern zwaar genoeg wordt, doet de zwaartekracht zijn werk weer en komt er een fusieproces op gang waarbij helium wordt omgezet in koolstof en zuurstof. Uiteindelijk ontstaat een schilstructuur als die van een ui, met lagen van zwaardere elementen dichter bij de kern. Sterren zwaarder dan acht zonmassa’s krijgen lagen van waterstof, helium, zuurstof, koolstof, neon, natrium en magnesium, en een kern van ijzer. Dit is hoe een groot deel van de zware atomen in onze wereld ontstaan.

Onder normale omstandigheden versmelt ijzer niet zodat ijzer zich ophoopt in de sterkern, totdat deze bezwijkt onder het eigen gewicht en er een kettingreactie op gang komt: een supernova. Dit zou moeten gebeuren bij alle sterren die zwaar genoeg zijn om ijzer in hun kern op te slaan. Over het algemeen is het zo dat hoe zwaarder de ster, hoe meer chemische elementen door de supernova-explosie worden verspreid in de ruimte, als zaden waaruit nieuwe sterren ontstaan. Het is nog altijd een mysterie waarom sterrenkundigen steeds meer bewijs vinden dat dit niet opgaat voor sterren die zwaarder zijn dan achttien stermassa’s.

Publicatie

Junjie Mao, Ping Zhou, Aurora Simionescu, Yuanyuan Su, Yasushi Fukazawa, Liyi Gu, Hiroki Akamatsu, Zhenlin Zhu, Jelle de Plaa, Francois Mernier, and Jelle S. Kaastra, ‘Elemental Abundances of the Hot Atmosphere of Luminous Infrared Galaxy Arp 299‘, Astrophysical Journal Letters. DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac1945.

Astronomers find new clue that heavy stars don’t go supernova

Conventional theory states that light stars like our Sun gently blow off their layers when they die, while heavy stars explode as a supernova. But for some reason, we are so far failing to find supernovae from stars heavier than eighteen solar masses. Now a team led by SRON astronomers finds a new clue that fuels this apparent mystery. Publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The research team looked at the luminous infrared galaxy Arp 299 using the X-ray telescope XMM-Newton. Their aim was to measure the abundances of several different chemical elements that are normally produced and expelled into space when massive stars explode. They found a mismatch for the heavier elements iron, neon and magnesium compared to existing models for how stars enrich their environment. ‘This is another indication that the very heavy stars don’t go supernova,’ says lead author Junjie Mao (Hiroshima/Strathclyde/SRON). When the researchers compared the measured amounts of iron, neon and magnesium with existing model calculations that describe how stars enrich their environment, the results appeared to be quite different. ‘If we remove the expected contribution from supernovae with masses above 23-27 solar masses to the chemical enrichment from the model calculations, the difference between our model and our observations is suddenly a lot smaller.’

Astronomers still don’t understand why stars from around eighteen solar masses would disobey the conventional theory of stellar evolution and refuse to go supernova. ‘One possible explanation is that they immediately collapse into a black hole, without the explosion,’ says co-author Aurora Simionescu (SRON). ‘We have now found more evidence that the end of life of massive stars could look very different than we thought so far. It could be more of a quiet passing away than a big cosmic fireworks show.’

Stellar evolution

When a star is born, it consists of mostly hydrogen, the lightest element in the Universe. The immense gravity builds up pressure in the core, igniting nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. This continues as a burning shell moving outwards, leaving a core of helium. When this core gets massive enough, gravity does its job again and ignites fusion of helium into carbon and oxygen. Eventually, you get a layered onion structure with increasingly heavier elements towards the center. Stars above eight solar masses get layers of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, carbon, neon, sodium and magnesium, and an iron core. This is how a large part of the heavier atoms in our world are made.

Iron doesn’t fuse under normal circumstances, so it piles up in the core, until it collapses under its own weight, igniting a chain reaction—a supernova. This should happen to all stars that are massive enough to build up iron at their core; and, generally, the more massive the star, the more chemical elements its supernova explosion should spread out into space, sowing the seeds for new planets. It’s still a mystery why astronomers are now finding more and more evidence that this doesn’t hold up for stars above eighteen solar masses.

Publication

Junjie Mao, Ping Zhou, Aurora Simionescu, Yuanyuan Su, Yasushi Fukazawa, Liyi Gu, Hiroki Akamatsu, Zhenlin Zhu, Jelle de Plaa, Francois Mernier, and Jelle S. Kaastra, ‘Elemental Abundances of the Hot Atmosphere of Luminous Infrared Galaxy Arp 299‘, Astrophysical Journal Letters. . DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac1945.