(English follows Dutch)

Een van de eigenschappen die een planeet geschikt maakt voor leven is de aanwezigheid van een weersysteem. Exoplaneten staan te ver weg om zoiets te zien, maar astronomen kunnen wel zoeken naar stoffen in de atmosfeer die een weersysteem mogelijk maken. Onderzoekers van SRON en de RUG hebben nu op exoplaneet WASP-31b een indicatie gevonden voor chroomhydride, dat bij de betreffende temperatuur en druk op de grens zit tussen vloeistof en gas. Publicatie in Astronomy & Astrophysics op 3 februari.

Terwijl ruimtesondes de planeten en manen rond onze Zon afspeuren naar buitenaards leven, zijn er in ons melkwegstelsel nog eens honderden miljarden andere sterren waarvan het merendeel waarschijnlijk ook omringd is door planeten. Die zogenoemde exoplaneten zijn te ver weg om naartoe te reizen, maar we kunnen ze wel bestuderen met onze telescopen. Hoewel de ruimtelijke resolutie meestal onvoldoende is om een exoplaneet in beeld te brengen, kunnen astronomen alsnog veel informatie halen uit de vingerafdrukken die hun atmosfeer achterlaat in het licht van de moederster.

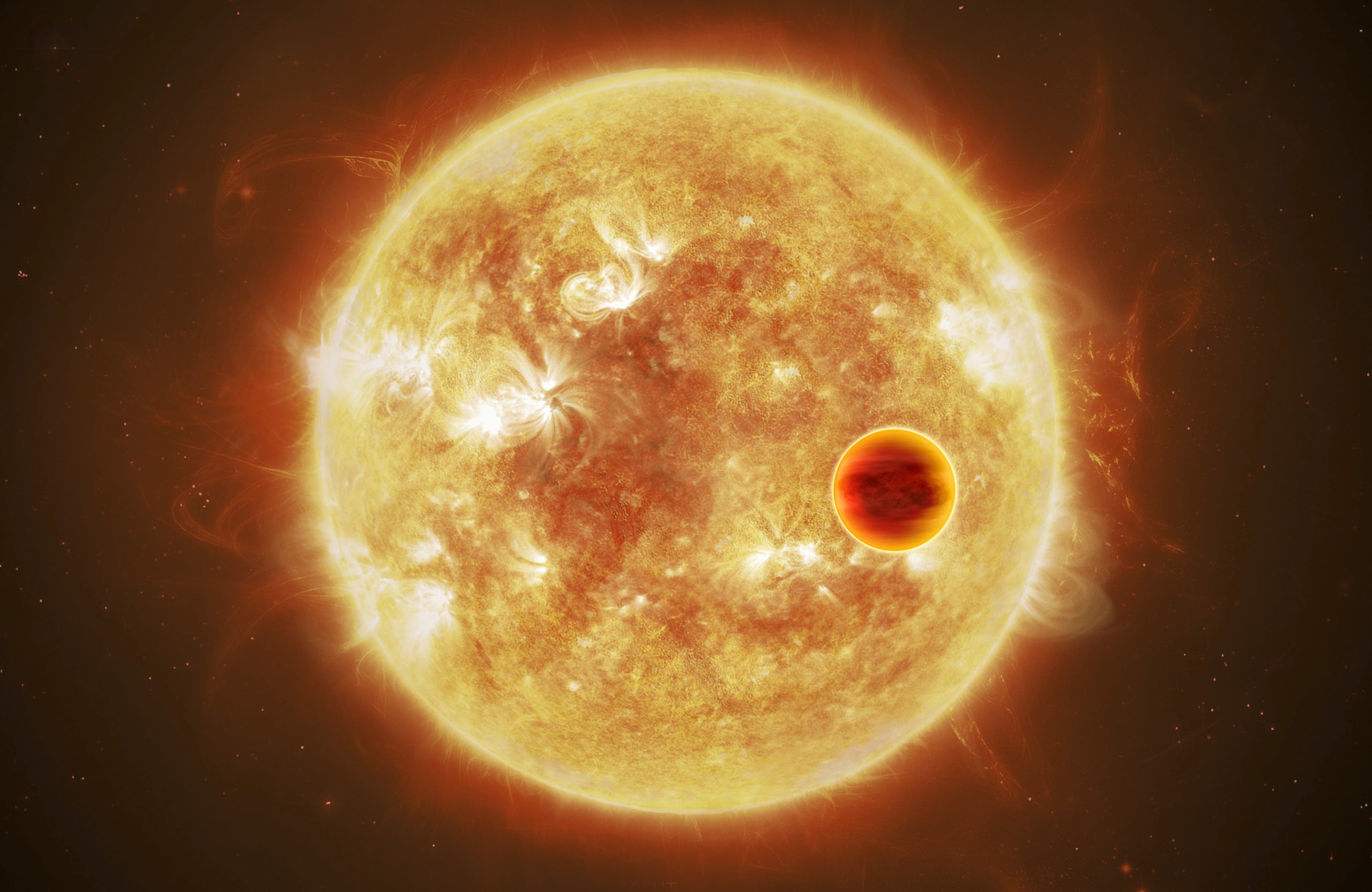

Sterrenkundigen leiden uit die vingerafdrukken—zogeheten transmissiespectra—af welke stoffen er in de atmosfeer van een exoplaneet zitten. Die zouden ooit een aanwijzing voor buitenaards leven kunnen geven. Of ze kunnen aantonen dat er een voorwaarde voor leven aanwezig is, zoals een weersysteem. Vooralsnog is dit soort onderzoek echter beperkt tot reuzenplaneten die dichtbij hun ster staan, zogenaamde hete Jupiters. Deze planeten zijn te heet om leven te verwachten, maar kunnen ons al veel leren over de werking van mogelijke weersystemen. Een onderzoeksteam van SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research en Rijksuniversiteit Groningen heeft nu een hint gevonden van een stof die op het randje zit tussen vloeistof en gas. Op Aarde doet dat denken aan wolken en regen.

Eerste auteur Marrick Braam en zijn collega’s vonden via Hubble-data indicaties van chroomhydride (CrH) in de atmosfeer van exoplaneet WASP-31b. Dat is een hete reuzenplaneet met een temperatuur van ongeveer 1.200 °C in de schemerzone tussen dag en nacht—de plek waar het sterlicht door de atmosfeer naar de Aarde vliegt. En dat is toevallig rond de temperatuur waarop chroomhydride overgaat van vloeibaar naar gas bij de betreffende druk in de buitenlagen van de planeet, vergelijkbaar met de omstandigheden voor water op Aarde. ‘Chroomhydride kan een rol spelen in een mogelijk weersysteem op deze planeet, met wolken en regen,’ zegt Braam.

Het is de eerste keer dat chroomhydride wordt gevonden op een hete Jupiter, dus bij de juiste druk en temperatuur voor zo’n weersysteem. Braam: ‘We moeten er wel bij aantekenen dat we alleen met ruimtetelescoop Hubble chroomhydride vonden. We zagen het niet in de data van de grondtelescoop VLT. Daar zijn logische verklaringen voor, maar we spreken daarom van een indicatie in plaats van een bewijs.’

Als de opvolger van de Hubble Space Telescope—de James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)—later dit jaar is gelanceerd, wil het team daarmee verder onderzoek doen. ‘Hete Jupiters, en dus ook WASP-31b, staan altijd met dezelfde kant richting hun moederster,’ zegt co-auteur en SRON-programmaleider Exoplaneten Michiel Min. ‘We verwachten daarom een dagzijde met chroomhydride in gasvorm en een nachtzijde met vloeibare chroomhydride. Volgens theoretische modellen zorgt het grote temperatuurverschil voor sterke winden. Dat willen we gaan bevestigen met observaties.’

Floris van der Tak (SRON/RUG), eveneens co-auteur: ‘Met JWST gaan we op zoek naar chroomhydride op tien planeten met verschillende temperaturen, om beter te begrijpen hoe de weersystemen op die planeten van de temperatuur afhangen.’

Publicatie

Marrick Braam, Floris F. S. van der Tak, Katy L. Chubb, and Michiel Min, ‘Evidence for chromium hydride in the atmosphere of hot Jupiter WASP-31b’, Astronomy & Astrophysics

Credit image: ESA/ATG medialab, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Evidence for substance at liquid-gas boundary on exoplanet WASP-31b

One of the properties that make a planet suitable for life is the presence of a weather system. Exoplanets are too far away to directly observe this, but astronomers can search for substances in the atmosphere that make a weather system possible. Researchers from SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and the University of Groningen have now found evidence on exoplanet WASP-31b for chromium hydride, which at the corresponding temperature and pressure is on the boundary between liquid and gas. Publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics on February 3rd.

While space probes scan the planets and moons around our Sun for extraterrestrial life, there are hundreds of billions of other stars in our galaxy, most of which probably also surrounded by planets. These so-called exoplanets are too far away to travel to, but we can study them with our telescopes. Although the spatial resolution is usually insufficient to make a picture of an exoplanet, astronomers can still get a lot of information from the fingerprints the atmosphere leaves behind in the light rays of the host star.

From those fingerprints—so-called transmission spectra—astronomers deduce which substances are in the atmosphere of an exoplanet. Those could one day give an indication of extraterrestrial life. Or they can show that there is a condition for life, such as a weather system. For the time being, however, this type of research is limited to giant planets close to their stars, so-called hot Jupiters. These planets are too hot to expect life, but they can already teach us a lot about how possible weather systems work. A research team from SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and the University of Groningen has now found evidence for a substance at the boundary between liquid and gas. On Earth this is reminiscent of clouds and rain.

First author Marrick Braam and his colleagues found evidence in Hubble data for chromium hydride (CrH) in the atmosphere of exoplanet WASP-31b. This is a hot Jupiter with a temperature of about 1,200 °C in the twilight zone between day and night—the place where starlight travels through the atmosphere towards Earth. And that happens to be around the temperature at which chromium hydride transitions from liquid to gas at the corresponding pressure in the outer layers of the planet, similar to the conditions for water on Earth. ‘Chromium hydride could play a role in a possible weather system on this planet, with clouds and rain,’ says Braam.

It is the first time that chromium hydride is found on a hot Jupiter and therefore at the right pressure and temperature. Braam: ‘We should add that we only found chromium hydride using the Hubble space telescope. We did not see it in the data from the ground telescope VLT. There are logical explanations for this, but we therefore use the term evidence instead of proof.’

When Hubble’s successor—the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)—is launched later this year, the team plans to use it for further investigation. ‘Hot Jupiters, including WASP-31b, always have the same side facing their host star,’ says co-author and SRON Exoplanets program leader Michiel Min. ‘We therefore expect a day side with chromium hydride in gaseous form and a night side with liquid chromium hydride. According to theoretical models, the large temperature difference creates strong winds. We want to confirm that with observations.’

Floris van der Tak (SRON/UG), also co-author: ‘With JWST we will be looking for chromium hydride on ten planets with different temperatures, to better understand how the weather systems on those planets depend on the temperature.’

Publication

Marrick Braam, Floris F. S. van der Tak, Katy L. Chubb, and Michiel Min, ‘Evidence for chromium hydride in the atmosphere of hot Jupiter WASP-31b’, Astronomy & Astrophysics

Credit image: ESA/ATG medialab, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO