Astronomen hebben voor het eerst twee enorme clusters van melkwegstelsels gevonden die op het punt staan om te botsen. De ontdekking vormt een van de ontbrekende puzzelstukjes in ons begrip van het ontstaan van structuur in het heelal. Grootschalige structuren —zoals melkwegstelsels en clusters van melkwegstelsels—lijken namelijk te groeien via botsingen en samensmeltingen. De ontdekking is vandaag gepubliceerd door Nature Astronomy.

Clusters zijn de grootste objecten in het heelal. Ze bestaan uit honderden sterrenstelsels die elk honderden miljarden sterren herbergen. Sinds de oerknal zijn clusters steeds verder gegroeid door te botsen en te versmelten met elkaar. Door hun enorme omvang—miljoenen lichtjaren in diameter—kunnen botsingen uitmonden in een miljard jaar durende paringsdans. Uiteindelijk blijft er één groter cluster over.

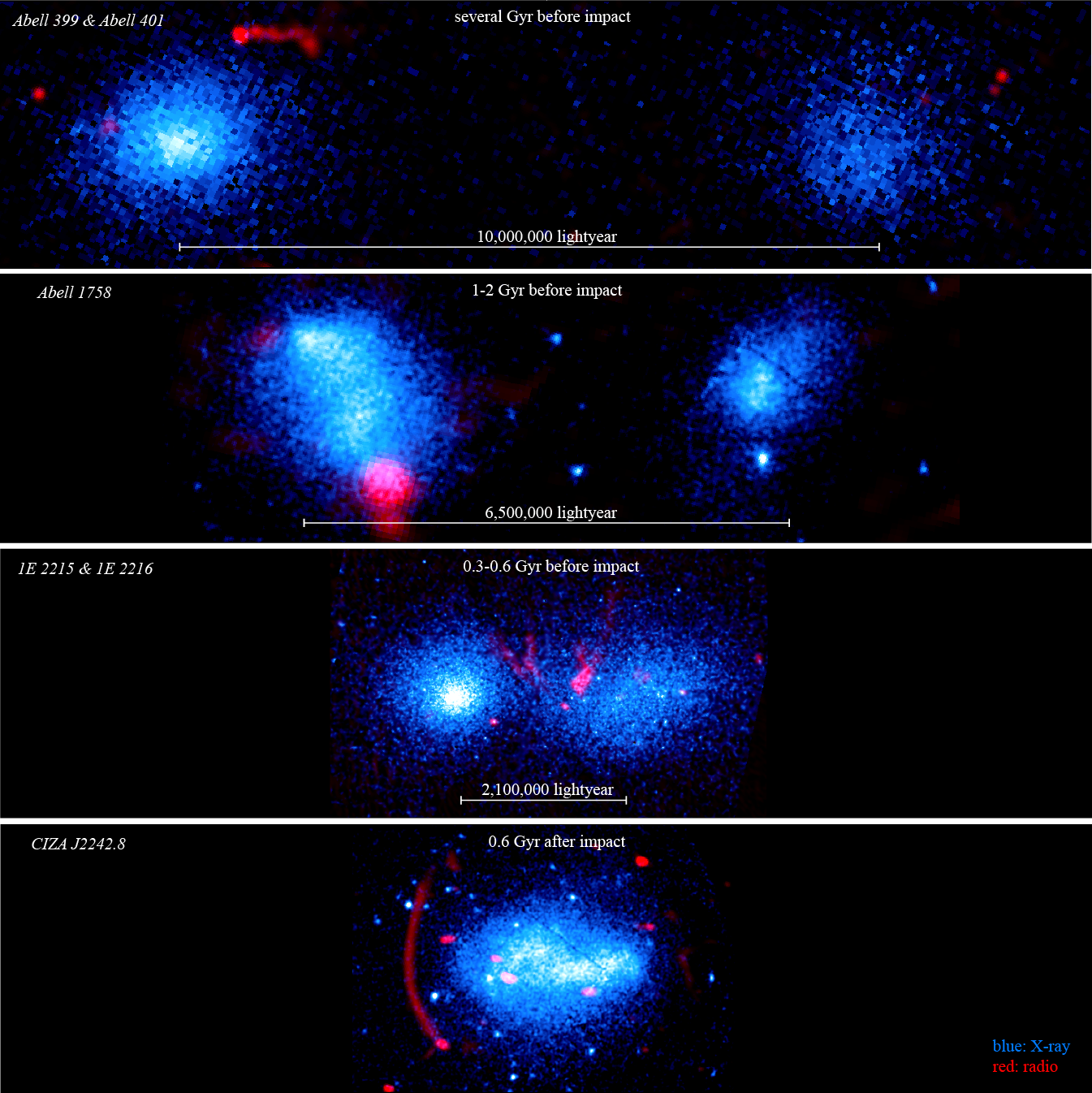

Omdat het samensmeltingsproces veel langer duurt dan een mensenleven, zien we alleen snapshots van de verschillende stadia van een botsing aan de sterrenhemel. De uitdaging is om botsende clusters te vinden die net bezig zijn met een eerste “kus” of aanraking. In theorie duurt die fase relatief kort en is hij dus moeilijk te vinden.

Schokgolf

Een internationaal team van astronomen heeft nu de ontdekking gepubliceerd van twee clusters die op het punt staan te botsen. Hiermee kunnen sterrenkundigen hun computersimulaties testen, die voorspellen dat er in het begin een schokgolf ontstaat tussen beide clusters, die zich loodrecht op de botsingsrichting voortplant. ‘De clusters die we hebben waargenomen geven het eerste duidelijke bewijs voor dit type schokgolf,’ zegt eerste auteur Liyi Gu van het Japanse RIKEN Laboratory en SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research. ‘De schokgolf heeft een gordel van gas met een temperatuur van 100 miljoen graden gecreëerd tussen de clusters. We verwachten dat de golf uiteindelijk ver in de buitengebieden van het cluster terecht zal komen en daar langzaam uitdooft.

Sterrenkundigen willen meer snapshots verzamelen om zo computermodellen te kunnen testen die de hele evolutie van clustersamensmeltingen beschrijven. SRON-onderzoeker Hiroki Akamatsu: ‘We gaan meer samensmeltende clusters zoals deze vinden met eROSITA. Dat is een röntgenmissie die de hele sterrenhemel in kaart brengt en medio juli wordt gelanceerd. Twee andere toekomstige röntgenmissies, XRISM en Athena, gaan deze objecten bestuderen met state-of-the-art spectrometers, wat helpt om de rol van de clusterschokgolven in de structuurvorming beter te begrijpen.’

Campagne

Liyi Gu en zijn collega’s bestudeerden het botsende paar tijdens een observatiecampagne met drie röntgensatellieten (ESA’s XMM-Newton, NASA’s Chandra en JAXA’s Suzuka) en twee radiotelescopen (LOFAR, een Europees project onder leiding van ASTRON, en de Indiase Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope).

————————————————————————————-

————————————————————————————-

Galaxy clusters caught at first kiss

For the first time, astronomers have found two giant clusters of galaxies that are just about to collide. This observation is one of the missing pieces of the puzzle in our understanding of the formation of structure in the Universe, because large-scale structures—such as galaxies and clusters of galaxies—are thought to grow by collisions and mergers. The discovery is published today in Nature Astronomy.

Clusters of galaxies are the largest known bound objects and consist of hundreds of galaxies that each contain hundreds of billions of stars. Ever since the Big Bang, these objects have been growing by colliding and merging with each other. Due to their large size, with diameters of a few million light years, these collisions can take a billion years to complete. After the dust has settled, the two colliding clusters will have merged into one bigger cluster.

Because the merging process takes much longer than a human lifetime, we only see snapshots of the various stages of these collisions. The challenge is to find colliding clusters that are just at the stage of first touching each other. In theory, this stage has a relatively short duration and is therefore hard to find.

Shockwave

Now an international team of astronomers announces the discovery of two clusters at the verge of colliding. This enables astronomers to test their computer simulations, which predict that in the first moments a shock wave is created in between the clusters and travels out perpendicular to the merging axis. “These clusters show the first clear evidence for this type of merger shock”, says first author Liyi Gu from the Japanese RIKEN laboratory and SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research. “The shock created a hot belt region of 100-million-degree gas between the clusters, which is expected to extend up to, or even go beyond the boundary of the giant clusters. Therefore the observed shock has a huge impact on the evolution of galaxy clusters and large scale structures.”

Astronomers are planning to collect more ‘snapshots’ to ultimately build up a continuous model describing the evolution of cluster mergers. SRON-researcher Hiroki Akamatsu: “More merger clusters like this one will be found by eROSITA, an X-ray all-sky survey mission that will be launched in July. Two other upcoming X-ray observatories, XRISM and Athena, will observe these objects with state-of-art X-ray spectrometers which helps us understand the role of these colossal merger shocks in the structure formation history.”

Campaign

Liyi Gu and his colleagues studied the colliding pair during an observation campaign, carried out with three X-ray satellites (ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite, the NASA’s Chandra satellite, and JAXA’s Suzaku satellite) and two radio telescopes (LOFAR, a European project led by ASTRON, and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope operated by National Centre for Radio Astrophysics of India).

The figure above shows the process of merging by putting together a set of different merger stages, ordered by the core-to-core distances. X-ray images (blue) are overlaid with radio images (red). The third row from the top shows the ‘first kiss’.