(English follows Dutch)

Geologische methaanbronnen kunnen menselijk of natuurlijk zijn, zoals de olie-industrie of moddervulkanen. Grondmetingen en TROPOMI-metingen aan de Javaanse moddervulkaan Lusi laten nu zien dat de natuurlijke geologische uitstoot waarschijnlijk groter is dan gedacht. Dan zouden we een kleiner aandeel toeschrijven aan menselijke geologische bronnen. Aan de andere kant komt er dan weer meer uitstoot voor rekening van andere menselijke activiteiten, zoals rijstvelden en veehouderij. Publicatie in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

Na koolstofdioxide is methaan het belangrijkste gas waarmee we onbedoeld het broeikaseffect versterken. Op dit moment stoten menselijke activiteiten en natuurlijke processen gezamenlijk 560 miljoen ton methaan per jaar uit. Toen de natuur nog het monopolie had op methaanuitstoot lag de emissie op 40% van het huidige niveau, rond de 250 miljoen ton, zo is af te leiden uit luchtbellen die gevangen zitten in eeuwenoud ijs. Mensen genereren methaanemissie via bijvoorbeeld rijstvelden, veehouderij, afvalverwerking en geologische bronnen zoals oliewinning. Natuurlijke bronnen zijn onder meer moerassen, de zeebodem en geologische bronnen zoals moddervulkanen.

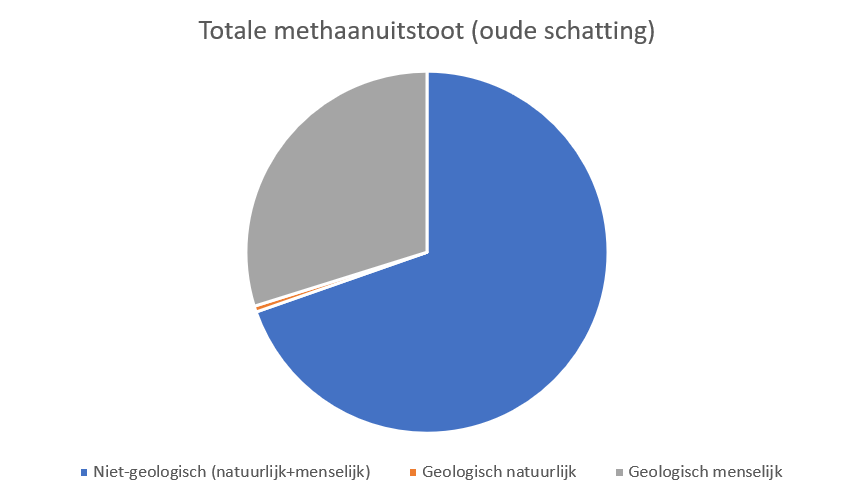

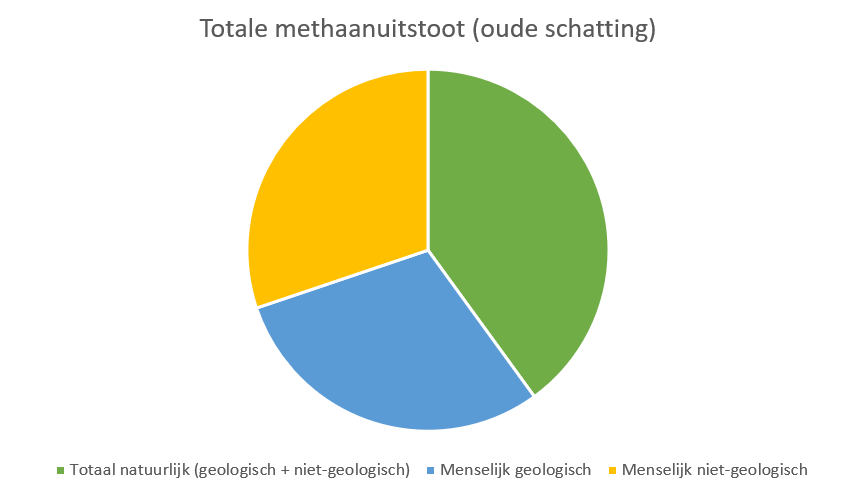

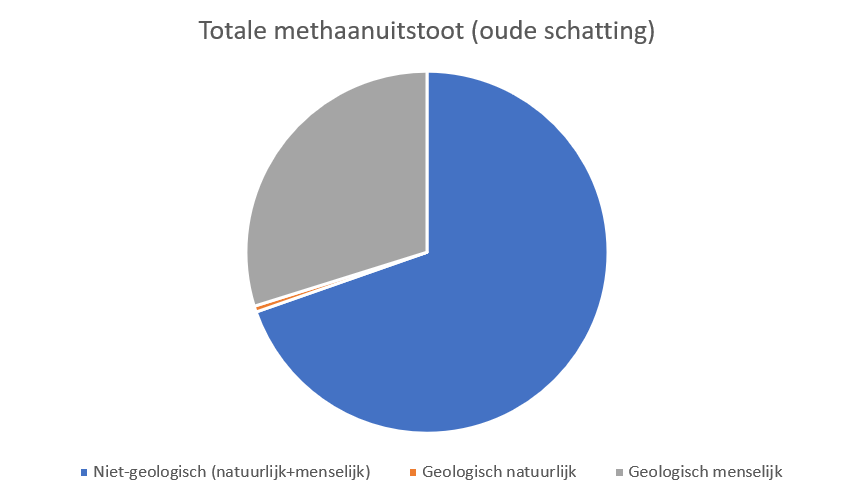

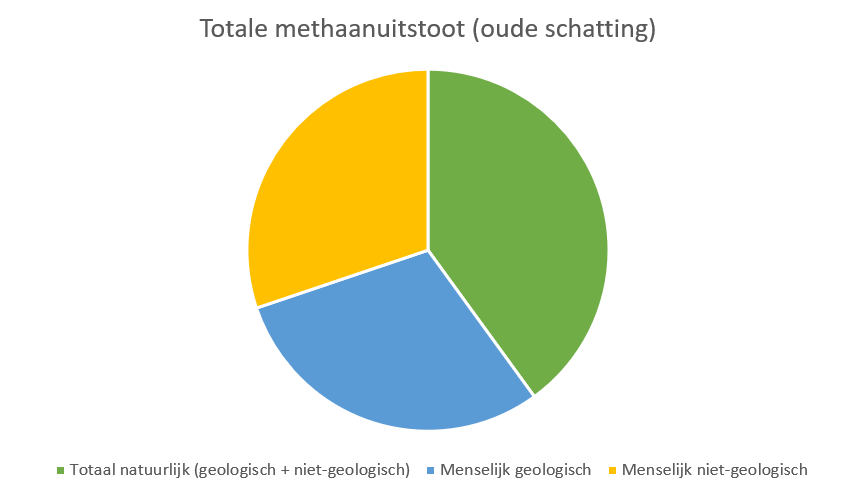

Geologisch methaan is te onderscheiden van methaan uit andere bronnen door een gebrek aan C14-isotopen. Dus de totale geologische uitstoot, menselijk plus natuurlijk, is bekend: 170 miljoen ton per jaar. Wetenschappers zijn daarom geïnteresseerd in moddervulkanen, want met een simpele aftreksom kom je zo ook meer te weten over methaanemissies uit de olie-industrie. De natuurlijke geologische uitstoot is lang geschat op 30-75 miljoen ton per jaar. Maar recente C14-metingen aan pre-industriële luchtbellen in ijs geven schattingen van 0,1 tot 5,4 miljoen ton. Dat zou dus een erg klein aandeel zijn in de 170 miljoen ton totale geologische uitstoot.

Een internationaal onderzoeksteam heeft nu met het Nederlandse ruimte-instrument TROPOMI vastgesteld dat één enkele moddervulkaan al aan de onderlimiet komt van schattingen voor de hele aarde—0,1 miljoen ton. Het gaat hier weliswaar om de grootste ter wereld, Lusi op Java, maar gezien het aantal moddervulkanen op aarde staat de natuurlijke geologische bron van methaan daardoor wel weer opnieuw op de kaart. ‘De vraag rijst of er iets mis kan zijn gegaan met de pre-industriële C14-metingen,’ zegt Sander Houweling, lid van het TROPOMI-team en verbonden aan ruimteonderzoeksinstituut SRON en de VU. ‘Afhankelijk van de uitkomst pakken de emissies door de olie-industrie dan hoger of lager uit.’ Omdat de totale menselijke methaanuitstoot vrij nauwkeurig bekend is, heeft dit ook consequenties voor de uitstoot die we toekennen aan andere menselijke activiteiten zoals rijstvelden, veehouderij en afvalverwerking.

Het onderzoek is een samenwerking tussen het TROPOMI-team, dat vanuit de ruimte data verzamelde, en wetenschappers die op Java zelf metingen hebben verricht. Houweling: ‘Zo kunnen we grond- en satellietmetingen met elkaar vergelijken. De resultaten van beide onderzoeken bevestigen elkaar, zodat we een betrouwbare conclusie kunnen trekken. Metingen vanaf de grond en vanuit de ruimte berusten op twee volledig verschillende methodes, die binnen onzekerheidsmarges op hetzelfde antwoord blijken uit te komen. De kans dat dat per toeval gebeurt is erg klein.’

Credit header image: Sigit Pamungkas/Reuters

Publicatie

Adriano Mazzini, Alessandra Sciarra, Giuseppe Etiope, Pankaj Sadavarte, Sander Houweling, Sudhanshu Pandey & Alwi Husein, ‘Relevant methane emission to the atmosphere from a geological gas manifestation’, Nature’s Scientific Reports

Natural geological methane emissions appear larger than expected

Geological methane sources can be either anthropogenic or natural, such as the oil industry or mud volcanoes. Ground-based measurements combined with TROPOMI observations on the Javanese mud volcano Lusi now show that the natural geological emissions are probably higher than expected. It would mean that we have to attribute a smaller share to man-made geological sources. On the other hand, other human activities should be held accountable for higher emissions, such as rice fields and livestock farming. Publication in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

After carbon dioxide, methane has the largest share in our unintentional amplification of the greenhouse effect. In this day and age, human activities and natural processes collectively emit 560 million tons of methane per year. Back when nature still had a monopoly on methane emissions, they were at 40% of the current level, around 250 million tons, as can be deduced from air bubbles trapped in ancient ice at the poles. Humans emit methane through, for example, rice fields, livestock farming, waste processing and geological sources such as oil extraction. Natural sources include swamps, the seabed and geological sources such as mud volcanoes.

Geological methane can be distinguished from general methane due to a lack of C14 isotopes. So the total geological emissions, human plus natural, is known. Scientists are therefore interested in mud volcanoes, because with a simple subtraction you can also learn more about methane emissions from the oil industry. Estimates of natural geological emissions have long been around 30-75 million tons per year. But recent C14 measurements in pre-industrial air bubbles in ice provide estimates of 0.1 to 5.4 million tons. So it would only account for a tiny portion of the 170 million tons of natural emissions in total.

An international research team has now used the Dutch TROPOMI space instrument to determine that a single mud volcano already reaches the lower limit of estimates for the entire Earth—0.1 million tons. Admittedly, we are talking about the largest in the world, Lusi on Java, but given the number of mud volcanoes on Earth, natural geological sources are back on the table as a substantial source of methane. ‘It raises the question whether something went wrong with the pre-industrial C14 measurements,’ says Sander Houweling, member of the TROPOMI team and affiliated with SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. ‘Depending on the outcome, emissions from the oil industry will be higher or lower.’ Because the total anthropogenic emissions are known fairly accurately, this also has consequences for the emissions that we attribute to other human activities such as rice fields, livestock farming and waste processing.

The study is a collaboration between the TROPOMI team, who collected data from space, and scientists who carried out measurements on the island of Java itself. Houweling: ‘That way we can compare ground-based and satellite measurements. The results of both studies are in agreement, so we can draw a reliable conclusion. Measurements from the ground and from space rely on two completely different methods, and still appear to arrive at the same answer within uncertainties. Chances of that happening by accident are very small.’

Credit header image: Sigit Pamungkas/Reuters

Publication

Adriano Mazzini, Alessandra Sciarra, Giuseppe Etiope, Pankaj Sadavarte, Sander Houweling, Sudhanshu Pandey & Alwi Husein, ‘Relevant methane emission to the atmosphere from a geological gas manifestation’, Nature’s Scientific Reports