Astronomen van onder meer SRON en de Sterrewacht Leiden hebben met ESA’s ruimtetelescoop XMM-Newton gas gevonden dat een van de puzzelstukjes vormt om de totale hoeveelheid ‘normale’ materie in het heelal in kaart te brengen. Publicatie in Nature op 21 juni.

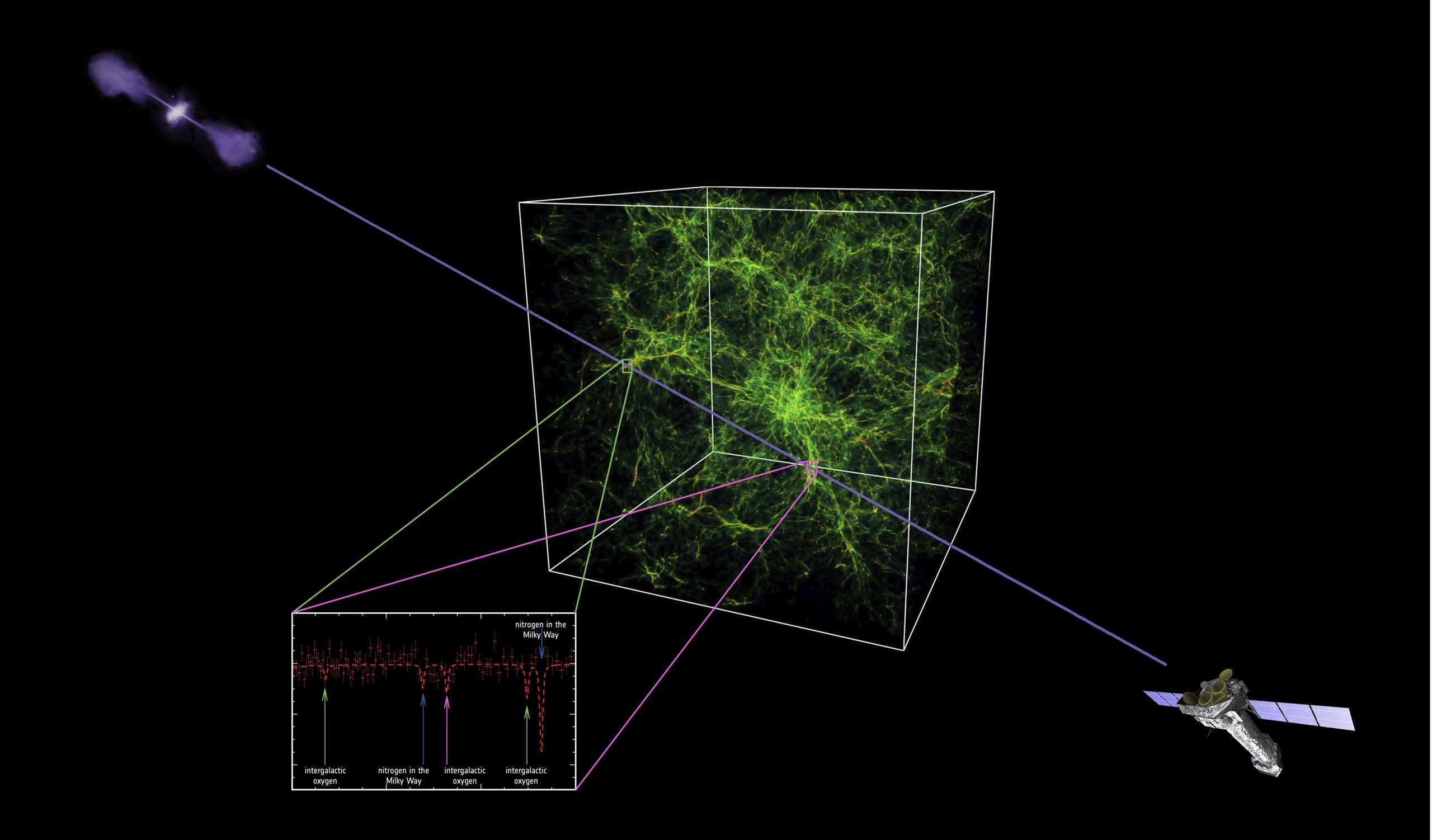

Artistieke impressie van het warm-hete intergalactische medium, een mix van gassen met temperaturen die uiteenlopen van honderdduizenden tot miljoenen graden, in de filamenten van het kosmische web. Credit: Illustrations and composition: ESA / ATG medialab; data: ESA / XMM-Newton / F. Nicastro et al. 2018; cosmological simulation: R. Cen

Het heelal bestaat voor respectievelijk vijfentwintig en zeventig procent uit mysterieuze donkere materie en donkere energie. Slechts vijf procent is ‘gewone’ materie, dingen die wij kunnen zien, zoals sterren, planeten en mensen. Maar zelfs die vijf procent is moeilijk op te sporen. De totale hoeveelheid normale materie, die astronomen baryonen noemen, kan worden geschat op basis van de kosmische achtergrondstraling, het oudste licht in het heelal, dat afkomstig is uit de periode van slechts 380.000 jaar na de oerknal.

Via waarnemingen aan verafgelegen sterrenstelsels kunnen sterrenkundigen de evolutie van baryonische materie volgen gedurende de eerste paar miljard jaar van het heelal. Daarna lijkt bijna de helft spoorloos. Eerste auteur Fabrizio Nicastro (Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), Italië) noemt deze vermiste baryonen een van de grootste mysteries uit de moderne astrofysica. “We weten dat de materie er moet zijn, maar we hebben er geen greep op. Waar is het gebleven?”

Als je alle sterren en sterrenstelsels in het heelal bij elkaar optelt, inclusief het interstellaire gas, kom je op ongeveer tien procent van alle normale materie. Als je daar het hete diffuse gas in de halo’s rond sterrenstelsels aan toevoegt, plus het nog hetere gas in clusters van sterrenstelsels, blijf je steken op nog geen twintig procent. Dat is op zich geen verrassing, want sterren, sterrenstelsels en clusters worden gevormd in de dichtste knopen van het kosmische web, de draadachtige groteschaalstructuur van het heelal, en die zijn zeldzaam.

Astronomen denken dat de ‘vermiste’ baryonen zich schuilhouden in de filamenten van het kosmische web, waar de materie ijler is en dus lastiger waarneembaar. Tot nu toe is slechts zestig procent van deze intergalactische materie gelokaliseerd.

Nicastro en zijn collega’s hebben in 2015 en 2017 in totaal 18 dagen lang met ESA’s röntgentelescoop XMM-Newton gekeken naar een quasar op vier miljard lichtjaar afstand. Quasars zijn grote sterrenstelsels met een superzwaar zwart gat in het centrum en schijnen helder op röntgen- en radiogolflengten. In de data vonden de onderzoekers de vingerafdruk van zuurstof in het hete intergalactische gas tussen ons en de verre quasar, op twee locaties langs de zichtlijn. Tweede auteur Jelle Kaastra (Ruimteonderzoeksinstituut SRON): “Er liggen daar enorme voorraden aan materie, waaronder zuurstof, in de hoeveelheden die we verwachtten. Het lijkt erop dat we eindelijk het raadsel van de vermiste baryonen kunnen oplossen.”

Het resultaat is het begin van een nieuwe zoektocht. De astronomen gaan nu met zowel XMM-Newton als NASA’s Chandra-observatorium nieuwe quasars onderzoeken. Co-auteur Nastasha Wijers (promovenda aan de Sterrewacht Leiden): “We willen nu naar andere bronnen in het heelal gaan kijken om te kunnen bevestigen dat onze resultaten universeel zijn. Ook willen we de langgezochte materie verder gaan onderzoeken.” Co-auteur Joop Schaye (Sterrewacht Leiden) voegt daaraan toe: “Dit is een spannende eerste stap. We kijken ook uit naar de lancering van Athena in 2031 waarmee we door de veel grotere gevoeligheid het warme intergalactische medium tot in groot detail kunnen bestuderen.”

————————————————————————————————————————————-

XMM-Newton finds missing intergalactic material

Astronomers including scientists from SRON and Leiden Observatory have found intergalactic gas which forms one of the missing pieces of the puzzle to map the total amount of ‘normal’ matter in the Universe. Publication in Nature on June 21st.

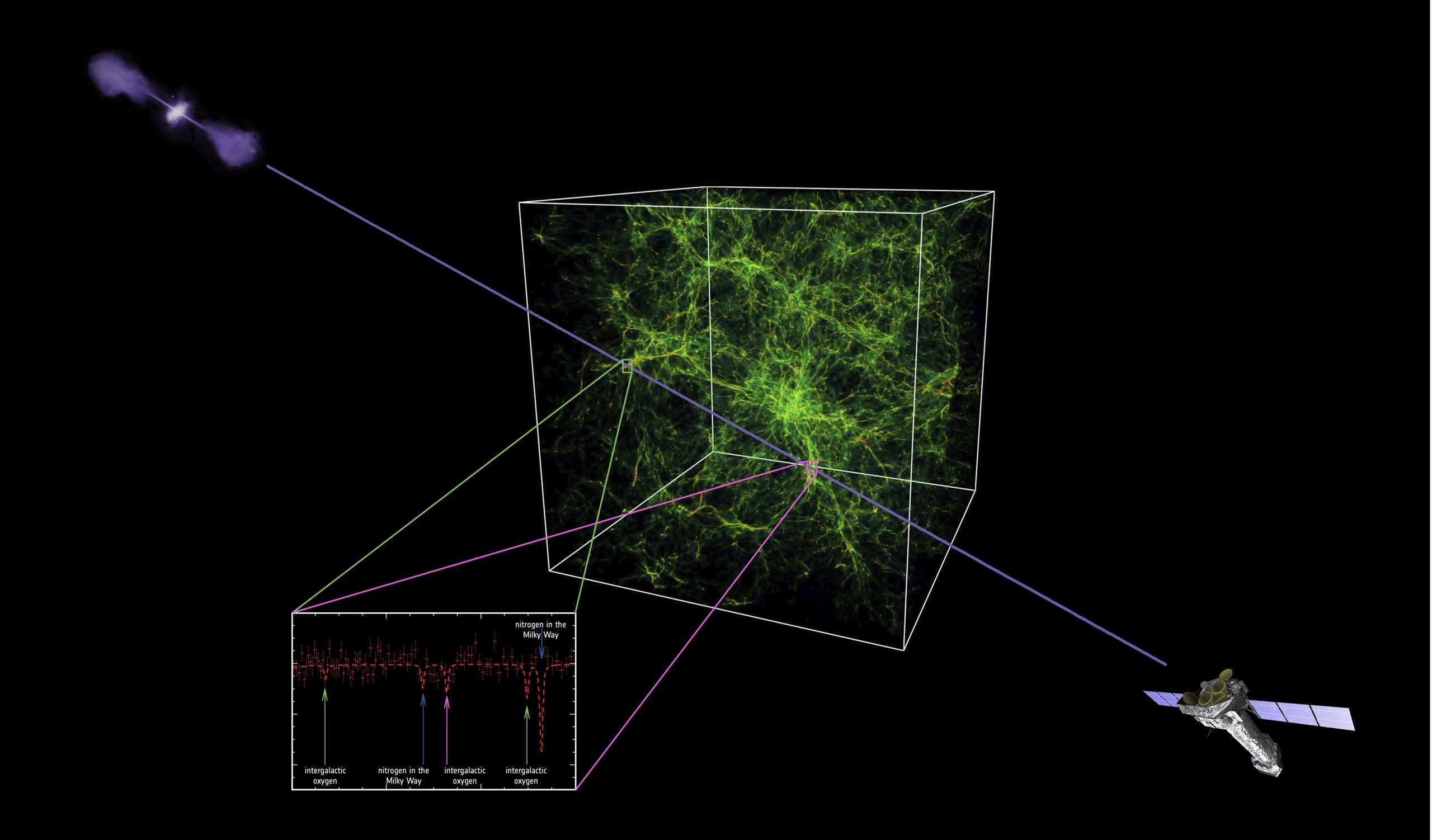

Artist’s impression of the warm-hot intergalactic medium—a mix of gases at temperatures varying from hundreds of thousands to millions of degrees, in the filaments of the cosmic web. Credit: Illustrations and composition: ESA / ATG medialab; data: ESA / XMM-Newton / F. Nicastro et al. 2018; cosmological simulation: R. Cen

The Universe consists of dark matter and dark energy for respectively twenty-five and seventy percent. Only five percent is ‘normal’ matter—things that we can see, such as stars, planets and people. But even those five percent are difficult to detect. Estimates on the total amount of normal matter—called baryons—are based on the cosmic microwave background. This is the oldest light in the universe, originating from 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Through observations of distant galaxies, astronomers are able to follow the evolution of baryonic matter during the first few billion years of the Universe. After that, almost half seems to be missing without a trace. First author Fabrizio Nicastro (Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), Italy) calls these missing baryons one of the greatest mysteries in modern astrophysics. “We know this matter must be out there, we see it in the early Universe, but then we can no longer get hold of it. Where did it go?”

If you add up all the stars and galaxies in the Universe, including the interstellar gas, you get about ten percent of all normal matter. If you add the hot diffuse gas in the halos around galaxies, plus the even hotter gas in clusters of galaxies, you are stuck with less than twenty percent. That is actually what you would expect, because stars, galaxies and clusters form in the densest knots of the cosmic web—the threadlike large-scale structure of the Universe—and those are rare.

Astronomers think that the ‘missing’ baryons are hiding in the filaments of the cosmic web, where matter is rarer and therefore more difficult to observe. Up to now, only sixty percent of this intergalactic matter has been localized.

In 2015 and 2017, Nicastro and his colleagues observed for a total of eighteen days with ESA’s X-ray telescope XMM-Newton, looking at a quasar at four billion light-years away. Quasars are large galaxies with a supermassive black hole in the center and they shine brightly at X-ray and radio wavelengths. In the data, the researchers found the fingerprint of oxygen in the hot intergalactic gas between us and the distant quasar, at two locations along the line of sight. Second author Jelle Kaastra (SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research): “Enormous stocks of matter are out there, including oxygen, in the quantities we expected. It seems that we can finally solve the mystery of the missing baryons.”

The result is the beginning of a new quest. The astronomers will now start investigating new quasars with both XMM-Newton and NASA’s Chandra observatory. Co-author Nastasha Wijers (PhD student at Leiden Observatory): “We now want to look at other sources in the Universe to confirm that our results are universal. We also want to look further into the newly found matter.” Co-author Joop Schaye (Leiden Observatory) adds: “This is an exciting first step. We are also looking forward to the launch of Athena in 2031, which allows us to study the warm intergalactic medium in great detail because of its much greater sensitivity.”