Important obstacle stardust cameras overcome

Fourier phase grating splits terahertz signal into eight beams

Research into interstellar atoms, molecules and molecular clouds can now make huge advances in the coming years thanks to rapid technological developments. An important intermediate step for the development of a supersensitive camera for research into this interstellar medium has now been realized: splitting a terahertz signal into eight beams.

If you want to investigate atoms and molecules in the interstellar medium then you should not make observations using ‘normal’ light, x-rays or ultraviolet light, but instead peer between the stars using a very specific type of infrared light: that in the terahertz range. The radiation at this specific wavelength contains the characteristic ‘fingerprints’ of various substances. The radiation in this region of infrared light is expressed as a frequency instead of a wavelength, with 1 THz being equivalent to a wavelength of 300 micrometers.

Special camera receivers called heterodyne receivers are needed to pick up this very specific terahertz radiation. Such a receiver mixes a signal from space with its own signal from a local oscillator. Hypersensitive mixer detectors can use the signal that remains to produce spectra. This approach allows such cameras to find the fingerprints sought with very high resolution.

Heterodyne cameras that have several pixels are necessary for the large-scale research into interstellar space that scientists want to carry out. That requires local oscillators that can generate a multiple signal. That is because space missions often do not have enough room for a separate oscillator for each pixel.

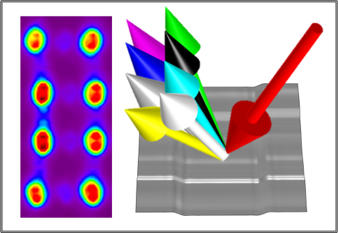

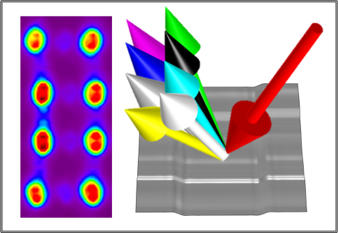

A PhD researcher at Delft University of Technology, Behnam Mirzaei, together with scientists from SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, has demonstrated such an oscillator with an eightfold output signal. The team shone a 1.4 terahertz signal through a Fourier phase grating that they had specially developed. This grating successfully split the incoming signal into eight beams. Furthermore, the researchers demonstrated the maximum theoretical efficiency: the ratio of incoming signal strength to the strength of the split signals. The researchers also discovered more about the influence of the incident angle.

This demonstration has opened up the way for the development of Fourier phase gratings for systems with several pixels at higher frequencies such as 4.7 terahertz – the unique ‘discovery area’ for certain chemical fingerprints.

NASA’s stratospheric balloon mission GUSTO, which is planned for 2021, will bring the Dutch camera system of SRON and Delft University of Technology with several pixels for 1.4, 1.9 and 4.7 terahertz to the edge of space for large-scale observation of molecules, atoms and molecular clouds between the stars of the Milky Way.

The researchers published the results in the international journal Optics Express, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.006581

This project was realized through a collaboration between Delft University of Technology, SRON, and the Arizona State University (USA).

Belangrijke hobbel sterrenstof camera’s getrotseerd

Fourier faseraster splitst THz signaal in achtvoudige bundel

Het onderzoek naar atomen, moleculen en moleculaire wolken in de ruimte tussen sterren, gaat de komende jaren grote stappen maken, dankzij snel voortschrijdende technologie. In de ontwikkeling van een supergevoelige camera voor onderzoek naar dit interstellaire medium, is nu een belangrijke tussenstap behaald: het splitsen van een zogenaamd terahertz (THz) signaal in een achtvoudige bundel.

Wie atomen en moleculen in het interstellair medium wil onderzoeken, moet niet (alleen) het ‘gewone’ licht, röntgenstraling, of uv-licht waarnemen, maar kan het beste tussen de sterren turen naar heel specifieke infrarood-straling. Om precies te zijn straling in het terahertz-gebied. In de straling van deze specifieke golflengte, zijn de kenmerkende ‘vingerafdrukken’ te vinden van diverse stoffen. In dit deel van het infrarood wordt straling uitgedrukt in frequentie in plaats van golflengte, waarbij 1 THz overeenkomt met 300 micrometer.

Om op de hele specifieke terahertz straling af te kunnen stemmen, zijn speciale camera-ontvangers nodig: heterodyne ontvangers. Zo’n ontvanger mengt het signaal uit de ruimte met een ‘eigen’ signaal uit een lokale oscillator. Van het signaal dat daarna overblijft, kunnen supergevoelige mixer detectoren spectra maken. Zo kunnen zulke camera’s de gezochte vingerafdrukken vinden, met een hele hoge resolutie.

Voor het grootschalige onderzoek dat wetenschappers willen naar de ruimte tussen sterren, zijn heterodyne camera’s nodig die beschikken over meerdere pixels. Daarvoor zijn dan ook lokale oscillators nodig die een meervoudig signaal kunnen geven. Want ruimtemissies hebben doorgaans geen plek voor een aparte oscillator voor elke pixel.

Een promovendus aan de TU Delft, Behnam Mirzaei, heeft samen met wetenschappers van SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research de werking van zo’n oscillator met achtvoudig uitgaand signaal aangetoond. Ze schenen een signaal van 1,4 terahertz door een speciaal door hen ontwikkeld zogenaamd Fourier faseraster, een ‘tralie’ die de straal met succes in acht bundels splitste. Bovendien toonde het onderzoek de maximale theoretische efficiëntie aan: de verhouding in kracht van het enkele signaal versus de gesplitste signalen. Ook kwamen de onderzoekers meer te weten over de invloed van de invalshoek.

Met de demonstratie is de weg geplaveid voor de ontwikkeling van Fourier faserasters voor systemen met meerdere pixels op hogere frequenties zoals 4,7 terahertz, de unieke ‘vindplaats’ van bepaalde chemische vingerafdrukken.

Stratosfeerballonmissie GUSTO van NASA zal in 2021 het Nederlandse camerasysteem van SRON en TU Delft met meerdere pixels voor 1,4, 1,9 en 4,7 terahertz naar de ruimterand brengen, voor een grootschalige waarneming van moleculen, atomen en moleculaire wolken tussen de sterren van de Melkweg

De onderzoekers publiceerden hun resultaten in het internationale vaktijdschrift Optics Express, van de Optical Society of America

Dit project was mogelijk door een samenwerking tussen TU Delft, SRON, en de Arizona State University (USA).